It is our choices, Harry, that show who we really are. Far more than our abilities.

J.K. Rowling

Great leaders make great choices. Mastering the art of impactful decision-making is, arguably, the most significant hallmark of successful leadership. Many have risen through the ranks on their ability to navigate their environments like second nature; their reflexes are honed through years of pattern recognition and skill development. When challenges appear in the crosshairs of their consciousness, their reactions can be swift and sure. Today, however, leaders are increasingly finding themselves in largely unfamiliar situations for which they have no map or reference points. The world is so complex and unpredictable that the instincts and practices that served some people for so long are often now incomplete, ineffective, or even dangerous. In addition, moving through constant disruption requires leaders to be far more collaborative than in the past. As a result, leaders need to learn new ways of reaching decisions. Some seem to be at a point of reckoning, as one client recently acknowledged: “If we want to reinvent our organization, we have to overcome our default ways of acting as soon as possible.” But how? This is the very real predicament many leaders need to address.

Generating “Way Power”

The change and growth that CEOs and other senior leaders need can only happen when they are intentional. We follow a process designed to broaden their leadership range to respond to the new situations they are increasingly facing and to help them stay agile as they navigate the journey ahead.

The central change-making vehicle of this framework is what we call the Options Generator. Dozens of research studies have shown that it is a combination of “Will power” and “Way power” that drives successful decisions. While the first is usually a given, without the second, success is less likely. Way power is the extent to which one can envision how to shape the future by devising at least four possible pathways forward. The research behind this was spearheaded by the late American psychologist Charles “Rick” Synder (with Shane J. Lopez and their teams) to demonstrate how people’s capacity to reach their desired goals can be attained by conceiving multiple pathways of possibilities, what Synder called “rainbows of the mind.”

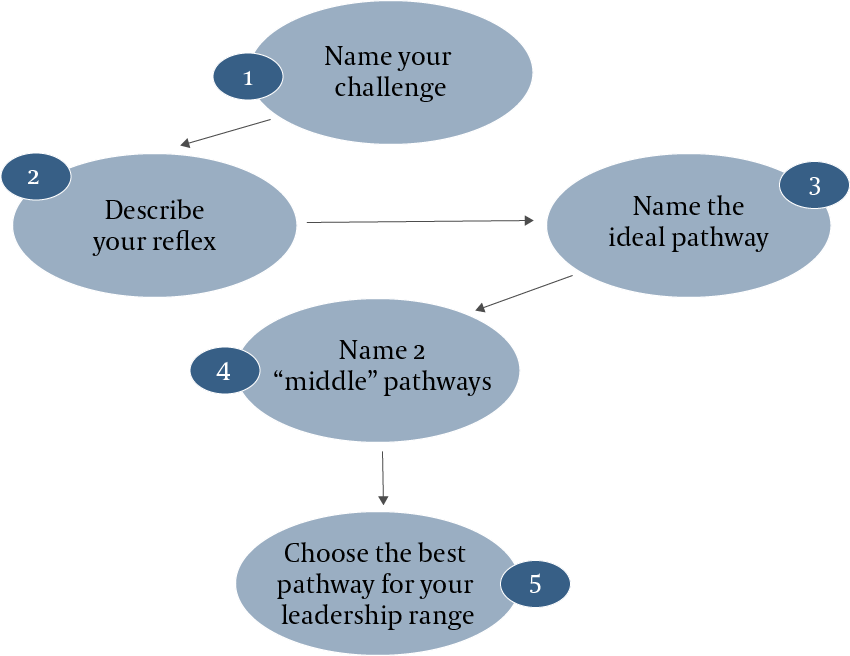

Five steps can take leaders through the process of devising options or alternative pathways to reach performance goals.

The Options Generator

Egon Zehnder 2021

-

Think about a challenge you are facing, and explicitly name it.

-

Now describe what your reflex is—what would your instant “go-to” moves be? Would you move fast or slow? Go big or small? Be collaborative or directive? Pause to really observe your reflex. The pause alone creates a powerful interruption in one’s thought process. That break provides the space needed to consider why that reaction may or may not be ideal at this juncture and to lay some groundwork toward creating and choosing alternatives.

-

In the moment of space you’ve created, identify what an optimal response could look like. Why would this be better? How does it compare to your reflex? When facing a challenge of a scale and scope that is unprecedented, or to drive a step change in leadership range, the optimal response will often be different from your reflex.

-

Now, try to find at least two more promising middle pathways that are between the reflex reaction and the optimal response. By this point, you will have conceived at least four ways to succeed. In many cases, the optimal response will require some coaching and may not be immediately obvious. The goal is to draft a range of responses that will create the opportunity to thoroughly evaluate the efficiency and feasibility of each and get you to deploy a pathway that is as close to optimal as possible.

-

Finally, commit to the best pathway within your leadership range. Once the decision is made, put a plan of communication and implementation into effect with your team and greater organization.

Case Study: Cultivating Collaboration

Let’s consider a recent example of a CEO we will call Cheryl Lind, who during her five-year tenure at a fast-moving consumer-goods brand led a quadrupling of the company’s revenues to $1 billion. She was known as a nurturer and a teacher who was well ahead of the curve—a customer trailblazer, someone who cleared obstacles, and who always “had her team’s back.” These were the characteristics that informed her leadership reflexes.

Right before the pandemic began, Cheryl moved to become CEO of another, much larger consumer brand. From the onset, it was clear that she would be facing very different leadership challenges given the timing of her move, the different and more complex issues facing the larger brand, and the new team she was leading. All of this required her, in a very short window of time, to adapt her style to work through others rather than with them, and to scale her leadership to calibrate to the new size of her company.

Cheryl was now at the helm of a larger team, half of whom were a great deal more experienced than those she had worked with in her previous role. Early on, tensions surfaced as Cheryl led with her reflex of teaching and being direct, specifically among the more seasoned team members who were seeking a thought partner. It quickly became clear that Cheryl would need to adapt her style to embrace more collaborative options.

To get there, Cheryl explored new leadership pathways that could expand her choices. Specifically, she and her team developed an overtly intentional approach in how they worked together while accessing their collective strengths, which proved to be pivotal in unlocking their full potential.

Here’s how it worked. Cheryl had one-on-one conversations with each of her direct reports and talked about what an ideal relationship would look and feel like from her perspective. As part of the same conversation, Cheryl asked each team member to also talk about what their ideal vision would be. She then gave a candid rating of where she thought the relationship was, and each team member did the same. From there, they all identified micro behaviors that could improve their teamwork over the ensuing four weeks. After that, they met monthly to continue to develop micro behaviors that would keep them moving toward the ideal relationship.

This joint work unleashed many new pathways for both Cheryl and her direct reports, including those with less experience. With the increased awareness it brought, Cheryl developed the ability to issue varying degrees of authority and collaboration certain situations and groupings required. As a result, she has at her disposal a leadership range aligned with the size and breadth of talent in her new organization.

Now, working so much more efficiently together, Cheryl and her teams are continuing to move through the pandemic to gain market share in an industry that remains in crisis, and they are setting their sights toward achieving their next ambitious growth target.

* * * * * *

Leading well in today’s complex world means being open to looking squarely at the question: “Who do I need to be right now?” And it means becoming willing and able to adjust the answers to shifting conditions and objectives, and to reach new critical decisions accordingly. Setting these intentions, combined with the behavior it generates, will create an integrated state of highly aware, agile leadership. With practice, leaders can move more easily and swiftly within the currents of incessant change and readily access the most fitting responses to maximize their performance goals.

< Volume 20

|

Volume 22 >

|