Boards are often reluctant to engage CEOs on their inevitable departure—even when the event may be imminent. Orchestrating succession timing feels like a complicated, delicate maneuver, even though discussing it should be part of business as usual. Highly effective boards ensure that succession planning never stops being a priority. It isn’t personal, it’s simply best practice. It takes many years to groom candidates. Developing leaders fit for the demands of today, requires long-term investment. Boards rely on a mature and well-balanced relationship between the Chair and the CEO. If power dynamics throw succession planning off course, the most effective boards summon the courage for the difficult yet vital task of putting the needs of the business first.

A Chair recently shared, “When I begin working with a new CEO, I make it clear that I will regularly engage with the non-executive board members without the CEO present. At least once a year, I will discuss the succession plan with the CEO and the board. This conversation should never be a surprise. And that means I make it clear from day one.”

We meet very few stakeholders who would disagree with the wisdom of this approach. Yet, CEO succession planning tends to involve more lip service than depth. As a result, boards are too often forced to contend with emergency timeframes.

Why Is This?

Real planning requires a level of rigor that can seem wildly ideal. Mounting burdens squeeze the board’s agenda—keeping their attention distracted from critical matters under the pressure to tick regulatory boxes. The discipline involved in maintaining a close eye on the leadership pipeline slides into the important-not-(yet)-urgent category. Boards put off the in-depth conversations and groundwork that underpins robust succession planning until later. But what is required calls for continuous effort—the training before you run your next marathon.

The only way to equip a board for the single most consequential decision it will ever make is to accept it as an ongoing priority.

Instead, many board members are lulled into the false belief that succession is no doubt in hand and that when the time comes, they will examine those names listed on a piece of paper. In our experience, this optimism sets up the board to get caught off guard. Many boards find themselves with too few, if any, viable CEO candidates when the time comes.

The Unforeseen Succession Crisis

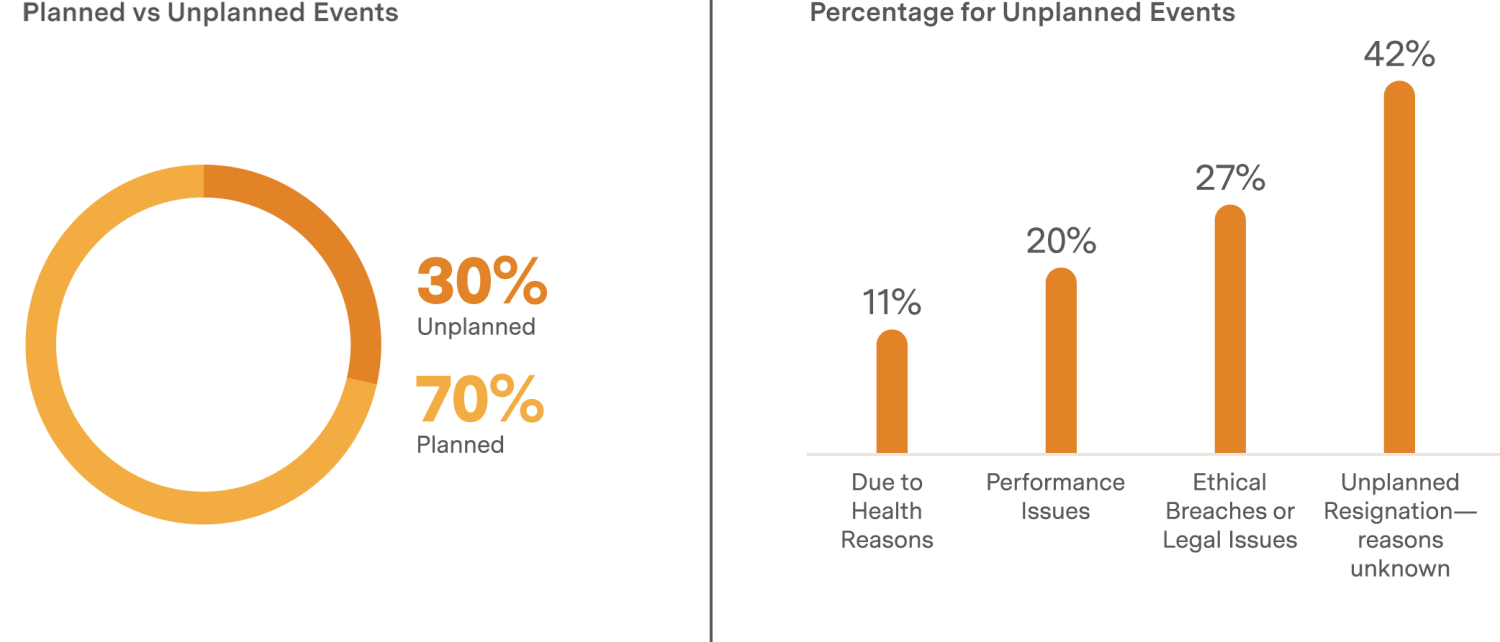

Nearly 1 in 3 CEOs will likely exit with little notice, leaving ill-prepared boards without a contingency plan.

In an analysis of 236 global companies with $30 billion or more in revenue and market capitalization, almost 1 in 3 lost their CEO in the last decade due to a major disruptive event. CEO ethical misconduct, poor business performance, and CEO illness explain over half of these shake-ups.

Natural Cycles of Leadership

Suppose you accept that even the most impressive CEO remains the best leader of the organization for a limited time—no more than two major cycles of strategic push and transformation, roughly eight years. Suppose you also accept that preparing the next generation of leaders demands a long game. You can never overprepare candidates or yourselves to orchestrate an inevitable transition. Then, the time to start planning is always yesterday.

How many long-tenured CEOs will go out on a high? There are natural cycles of leadership. There are only so many times you can rejuvenate yourself in the context of such an intense position. One Chair commented, “After eight successful years, it is too much to wish, never mind expect, that the same person can sustain this momentum.”

Sadly, in cases where organizations and boards enjoy a CEO who has delivered long-term performance, the risk that there is no contingency plan becomes even greater.

Cultivation Before Harvest—Invest Now to Produce Your Next CEO

While the CEO role has always required exceptional leadership, today’s geopolitical tensions, stark societal divides, disruptive technology, and environmental disasters—the so-called polycrisis, call for transformational levels of leadership. In our survey of 1,000 CEOs, a near-unanimous 97% told us that the demands of the role mean they must learn to transform themselves to transform their business.

The usual must-have “background experience” boards seek in potential candidates falls dramatically short of the leadership capacities today’s CEO must demonstrate. Yes, developing leaders entails assignments and postings designed to expose candidates to the breadth of the CEO’s remit. But boards must plunge deeper to align on the core leadership qualities the next CEO must possess.

It takes at least two, and preferably three years, to bring a robust slate of candidates to fruition. To do so entails much more than filling a gap. To unlock a leader’s potential, to cultivate CEO material, the developmental focus shifts from experience and skills to guiding already highly accomplished executives toward genuine self-leadership. Do they understand their blind spots and tendencies, know how to flex their style under stress, when to ground themselves, how and why to tap into a higher sense of purpose, what it takes to hone their relational capacities to create authentic followership?

Increased self-awareness paves the way to becoming an evolved version of oneself—a stage of leadership mastery we call vertical development. It requires deep work: intense self-reflection, sustained learning (with peers, coaches, or others), and deliberate investment.

Vertical development does not happen over a weekend or even a year. Leaders must stretch themselves in real-time, on the job, with opportunities to step back and take stock. In our experience, the real payoff, when a leader has put insight into fresh practice and enters a new realm of maturity, takes no less than two to three years.

Most boards struggle to accept that premise. Many do not see that we have entered a time when CEO-level leadership no longer develops naturally over the course of a successful career by being exposed to different experiences but must be intentionally built along the way.

Getting to Know the Real Candidates

In addition to the necessary developmental runway to groom the best people, anything less than two years denies board members the level of exposure to candidates they need before they can speak knowledgeably about concerns and hopes for the different personalities and capabilities each person brings.

Succession planning must always strike a balance between a tight yet inclusive process. Every board member should know their role—when and how they can expect to engage on the question of the next CEO. To be well-equipped for the final phase, boards must be able to have an open, informed dialogue not just about CEO candidates but the long-term health of the entire C-suite.

To achieve this, the best boards invest in a process where some (or, sometimes, all) members have a clear view of the development and exposure plan for every name on that list.

Nearly 30% of CEO transitions were considered major disruptions, with 27% of these instances involving CEOs being pushed out due to ethical lapses

Source: Based on 191 departing CEOs within 236 companies from 2014 to 2023.

Transformational Leaders

Transformational leaders are adaptive, humble, curious, and open.

They listen to a diverse set of perspectives and demonstrate exceptional relationship skills.

They cut through the noise, providing a deep sense of purpose and clarity of direction that inspires followership.

What Board Members Tell Us

In an analysis of 330 Board Reviews, conducted between 2021-2023, CEO succession appeared as their number one issue.

The Writing on the Wall

Eight years may be the ideal, but it’s time to replace the incumbent whenever there is…

- Ongoing unhappiness with business performance

- Declining organizational health, including frequent mentions of a toxic or fearful company culture

- Consistent noise about the CEO’s ethics or a personal style that destroys trust-based teamwork or vital relationships with key stakeholders (or symptoms of this, such as the departure of pivotal people)

- Waning CEO energy or motivation level.

Power Dynamics in Succession Planning

The relationship between the Chair and the CEO lies at the heart of good governance and, as the opening quote implies, comes to the fore in succession planning.

Who holds the most power? If the CEO is struggling, it is typically the Chair. If the business is struggling and the CEO has just been appointed, it tends to be the CEO. But in a well-performing company, it is unsurprising that the most influential person is the CEO. Hence, the most common dynamic we observe involves CEOs who control their departure.

Board members frequently tell us the number one issue they face with transition planning is not just the incumbent’s reluctance to go but to get started. CEOs who keep their boards at arm’s length prevent members from getting to know internal candidates. CEOs who hijack the process by muscling for their favored candidate—often a leader who resembles themselves. Not only does the exercise become far from inclusive and balanced, but the wrong hands hold the reigns.

In these ways, the best performing CEOs, when they obstruct succession, become a threat to the business. Success distorts vision. Power impairs objectivity. CEOs who have delivered excellent performance year-on-year can become blind to when their time must end. Boards (and shareholders) get dazzled by track records, only to shock themselves with the cold reality that they have been left without a viable candidate and a culture and organization shaped to fit the incumbent.

Mea Culpa: You Can Only Begin From Where You Are Now

Seizing the topic on day one of a new CEO carries enormous advantage. It presents the only moment when the succession topic remains impersonal.

The more time passes, the greater the risk that what would have been accepted as simply best practice becomes a delicate matter, one that destabilizes the status quo.

But failing to start the conversation early enough cannot excuse refusing to do so now. It takes considerable courage, perspective, and care for the Chair to interrupt this unhealthy dynamic.

When they do not, the most successful organizations have boards that can and will intervene.

Professional Friendship

As the organizational philosopher David Whyte reminds us, “Friendship is the great hidden transmuter of all relationships. The dynamic of friendship is almost always underestimated as a constant force in human life.”

In the very best cases, the Chair and the CEO form a well-tended partnership—one based on trust that balances autonomy with healthy reliance on one another. The ultimate guarantor of robust succession planning is the professional friendship between these two.

In such a friendship, both accept that the person is NOT the role. They discuss what’s expected from the CEO during and long before the transition. The Chair talks frankly with the CEO about what they are doing to develop internal candidates today.

Equally, the question of how and when to sequence the succession of the Chair vis-à-vis a CEO transition remains a pertinent calculation that mature Chairs wrestle over. While no simple mechanism exists to address this, the wisest boards create environments where egos can cope with tabling this high-stakes question.

In the United States, where it is common to have a CEO who is also the Chair, boards contend with a very different dynamic. They must rely on the Lead Independent Director to navigate CEO succession.

The Seasonal Shift

In continuous succession planning, the board shifts from cultivating to harvesting, from ongoing stewardship to a timetabled transition.

Deciding to trigger a transition often strikes boards as too bold a move, littered with risks that are best avoided. The timing seems a complicated, delicate maneuver. Board members fixate on the reputational fallout this process can set off: rumors in the market, dips in the share price, and uncertainty spreading throughout the C-suite.

These concerns are symptomatic of a deeper malaise. The temperature of the board’s attention has flipped from cold to hot—when the only safe path involves keeping it warm.

When we observe strong boards in action, in the most effectively governed organizations, healthy successions are never triggered—in that, there is no sudden “hot phase.” The planning and preparation never stopped. Boards simply change gears. They shift from the discipline of driving the process of cultivating leaders to a phase of selecting the best candidate to take on the job.

They do not depend on the incumbent to navigate the power transition—they guide and support incumbents to do so.

Board Health–Prerequisites

The most effective boards are collaborative, engaged, balanced in composition, and future oriented. These prerequisites enable a healthy approach to CEO succession planning:

Collaborative—Healthy boards comprise members who respect and trust one another. They operate with a spirit of shared ambition. They welcome open debate and rely on transparent dealings without needing overly political behind-the-scenes tactics.

Engaged—Boards that dedicate real time to CEO succession, gain the traction required for this responsibility. They overcome the tendency for boards to interact with each other too formally and get to the crux of critical matters. They avoid or remove members who sit on too many boards, who will struggle to feel the heat of deep-seated accountability.

Balanced—While boards need members who lend deep insight into technical topics and can benefit from members who join from academia, healthy board composition promotes a generalist perspective. Their experts ideally grew up in a business. Boards with too many specialized advisors get trapped in side-alleys and miss the larger business agenda. Healthy boards possess a breadth of commercial and organizational intelligence.

Future Oriented—With good reason, we meet CEOs who decry wasting precious time sitting in board meetings that seem hopelessly off-point and out-of-touch with the complexity of current challenges. Equally, we also meet board members who are “stuck in the now” and so attached to the current CEO’s agenda that they do not step back enough to question whether those goals reflect where the business must go. Strong CEO candidates must be prepared not to take over from the incumbent but to take forward the organization. This, in turn, depends on a board that has clarity about the mandate for a CEO who will have the future well within sight. A healthy board relies on rigorous discussion and debate to align on the company's strategic evolution and what capabilities they must seek (and sponsor the development of) in the next CEO.