Nominating committees must abandon old assumptions

The Landscape

Over the past year, several sizable pension funds and proxy advisory firms have taken a more aggressive stance on gender diversity in the boardroom, threatening to withhold votes or even mount an opposition slate at companies thought to be making insufficient progress on this issue. This level of action by investors outside the activist community brings a new level of urgency to boardroom gender diversity.

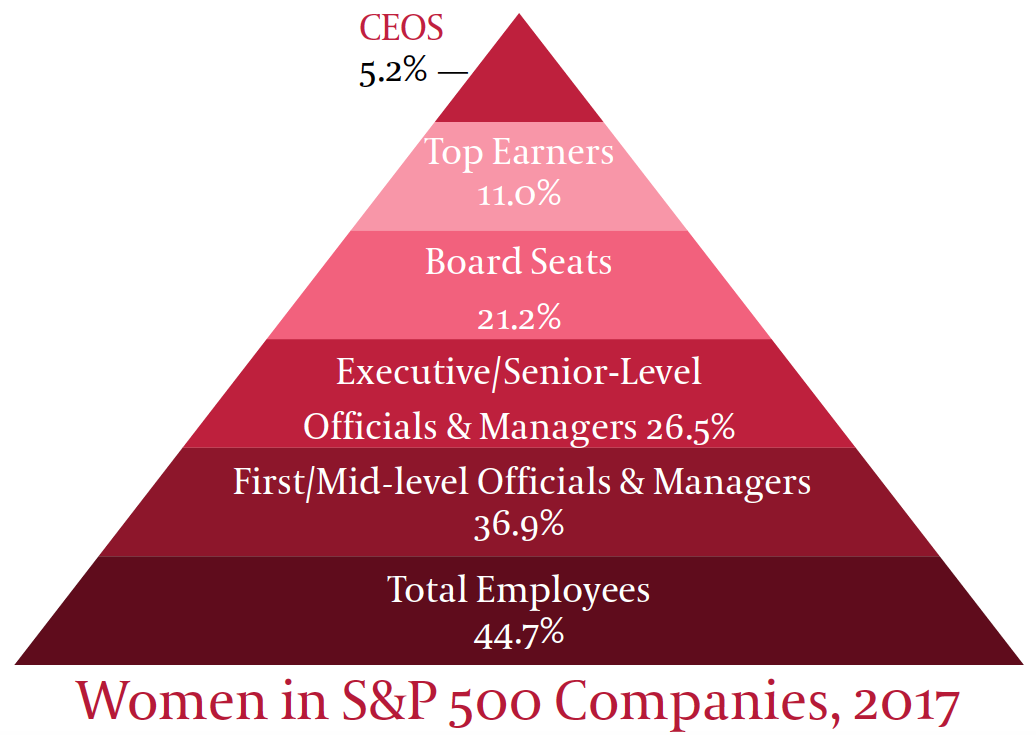

As leadership advisors to both management and boards, we play a tangible role in ensuring that the pool of candidates for directorships includes highly qualified women. So we are heartened when influential investors like CalPERS, CalSTRS, the New York State Common Retirement Fund and others make such strong commitments to having more women in the boardroom. But because we work closely with nominating committees to help them shape boards and fill board seats, we also know firsthand how committed the vast majority of boards are to greater gender diversity. Most of the board search assignments we take on these days make the selection of a director candidate who is a woman or member of another under-represented group an explicit priority. And some progress has been made. After more than five years of stagnation with only 2% growth, the percentage of board seats held by women at S&P 500 companies rose from 16.2 percent in 2012 to 21.2 percent in 20171.1

At the same time, more can be done – particularly if boards want to meet (and eventually surpass) the 30 percent benchmark that is emerging as the consensus target for gender diversity in the United States. Indeed, in our view, unless nominating committees alter their current strategies, the progress that has been made in the last five years is likely to slow long before that goal is reached. Consider that for S&P 500 boards to be 30 percent female, approximately 488 more director seats need to be held by women than is the case now. This is a considerable hurdle because many of the obvious choices – those women who have managed to check all the boxes that have traditionally been expected of a public-company director – are already serving on a board, if not more than one. We cannot, therefore, increase the number of seats held by women by returning to the same pool of female director candidates. Strengthening the pipeline of women on the CEO track will obviously enlarge this pool (see Figure 1). But seeing the benefits in the boardroom will take considerable time, if only because of the very limited number of vacant CEO slots to be filled at any moment. The math is clear, and no amount of pressure from investors will alter it.

Limiting assumptions and how to move past them

For nominating committees to break through this impasse, they need to rethink some of their implicit assumptions about what a board director should look like. We see those assumptions – which job titles are acceptable, what type of path defines a successful career and how well-known a director candidate should be to those already on the board – rear their heads when we work with boards on director succession and recruitment. It’s those assumptions, rather than a lack of good intentions, that are holding companies back from building more gender-balanced boards.

1. Consider those who have never been CEOs or even held P&L responsibility

This is perhaps the most universally held expectation, and it is understandable why. The CEO faces a unique set of pressures, which can only be fully understood by someone who has also experienced them. Similarly, “P&L responsibility” has long been shorthand for “responsibility for the overall health and viability of the enterprise,” and the world can be divided into those who have held that responsibility and those who have not.

The constant demand for board members with P&L responsibility, however, is based on an increasingly outdated view of the other executive committee positions. Not too long ago, the chief executive really was the “chief” of the organization, with the functional leaders playing essentially supporting roles. That is less and less the case today, in which virtually every C-suite member is expected to be a strategic business partner to the CEO and the CEO is more an orchestra conductor than a field commander. Increasingly, functions like marketing, supply chain and technology no longer merely support the business – they are the business, even if they don’t carry traditional P&L responsibility. Functional leadership holds a new level of importance and needs to be upgraded in the minds of nominating committees.

Nominating committees also need to broaden their view to consider those who have risen to leadership outside of corporate environments. Including investment bankers, consultants, academics and former government officials in the candidate pool can provide a wider range of contacts and perspectives while making that pool more diverse.

2. See the value in coloring outside the box

Boards naturally want directors who stand out from their peers in their leadership and insight, and it has long been assumed that such a leader can be identified by a seamless, ever-upward career trajectory of greater responsibility over more and more people – as if it is the trajectory, not the underlying experience or accomplishments, that validates the quality of the executive.

That the best leaders are those that rise the quickest and smoothest up the ranks of an organization has probably always been a questionable assumption, but it is especially shaky today, when the number of people one oversees has little bearing on impact, when careers are dotted with entrepreneurial ventures and when personal and professional lives are less siloed and more fluid. The career path of the people who are transforming businesses and industries – and who are needed on today’s boards to help companies manage new risks and opportunities – increasingly fails to follow a tidy script.

If a career trajectory of fits and starts describes the new generation of business leaders, it also describes the path that women have taken for decades. To balance career and family, many women have had to progress and develop in a non-linear fashion – not always by choice, but sometimes because it was the only option available to them. Whatever the gender of the candidate, boards need to move past the notion that only particular types of career paths are acceptable.

Doing so will require nominating committees to approach the task of identifying candidates with greater deliberation because they will no longer be able to rely on traditional markers of excellence. They will have to have a clear vision of the qualities they are looking for in a director based on the current competencies of the board, projected director turnover, and the strategic direction of the business. They will then need to dig beneath the CVs to objectively evaluate candidates based on a deeper understanding of the value they can add. This increased probing will make director evaluations more like management assessments in their depth and nuance.

3. Reach beyond your connections’ connections

For some time, nominating committees have realized that in an economy no longer built on industry silos, it is necessary to reach beyond one’s immediate professional network when defining the pool of director candidates. But our observation has been that while boards do look beyond their own networks, they typically don’t look very far. To construct boards with the range of qualities needed today, nominating committees must reach beyond their connections’ connections, and then be ready to invest the time necessary to develop these new relationships – we recommend at least one year before beginning the formal nomination process. Along with widening the director candidate pool, nominating committees should take a more deliberate approach to managing the director tenure cycle, allowing nominating committees to think more strategically about the competencies and perspectives that are needed on the board over a longer timeframe and thus plan accordingly. (For a more detailed look at strategically managing board composition, see Evergreen Board Succession Planning by Kim Van Der Zon and Claudia Pici-Morris in the September/October 2016 issue of The Corporate Board.)

Summary

The prospect of action by institutional investors on gender diversity won’t put the issue any higher on nominating committee agendas than it already is. But that increased pressure may prompt boards to think differently about the nominating process and thus set aside assumptions that are preventing further progress. This in itself will require effort on the part of today’s directors, who were nominated to their seats in a different time and most likely under a more informal and insular process. Nominating committees that take this step, however, will have a significant competitive advantage in recruiting directors and in building the gender-balanced boards that investors increasingly expect.

1 The Momentum Myth: The Impact of Turnover on Women’s Representation on Fortune 500 Boards, Catalyst, 2012