The new normal ushered in by COVID-19 has spurred Boards to reevaluate their succession plans and processes. This renewed focus is reminiscent of the change in approach toward leadership decisions made by company Boards following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). To get a better sense of how a crisis affects leadership planning, Egon Zehnder’s global Mining & Metals practice recently analyzed 40 mining CEO transitions that took place during the period 2000-2019 – at publicly traded companies in operation for at least 20 years with a market capitalization exceeding US$5B. We split our CEO succession analysis into two decade-long industry phases:

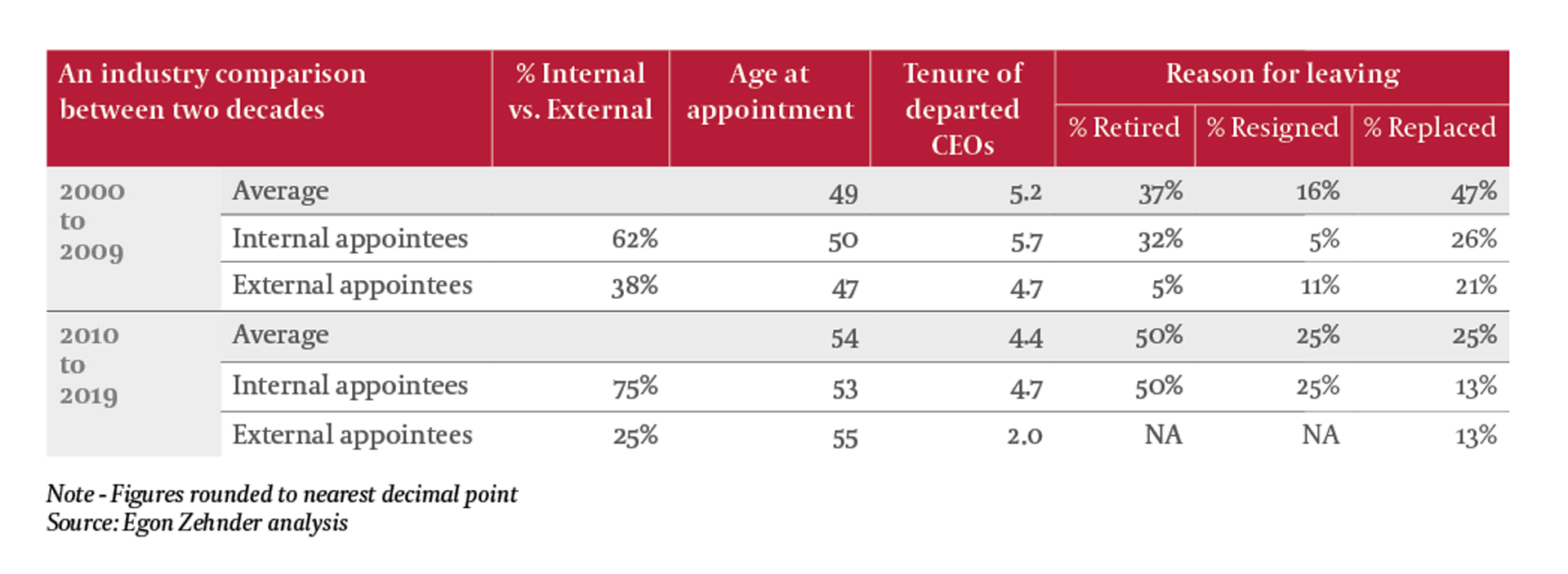

Markedly different sets of data emerged from our analysis, showing a distinct shift in CEO attributes between 2010-2019 and the prior 2000-2009 period. The average age of a CEO when appointed rose from 49 to 54 years old, and although average CEO tenure appears to have shortened from 5.2 years to 4.4 years – the latter average is derived from a relatively smaller number of CEOs who departed largely due to retirements in the last decade. There was also roughly a 13 percentage-point increase in internal appointments to 75 percent of all CEO hires during the period 2010-2019, indicating that Boards moved away from charismatic outsiders with experience and capabilities that did not always suit companies’ needs.

Although the factors driving these trends are complex and ever shifting, we believe that the GFC was a major inflexion point – not only impacting how companies make financial decisions today, but also influencing leadership decisions being made by mining company Boards. CEO appointments are one of the few variables over which Boards have complete control, and this is being taken more seriously – with the GFC serving as a cautionary tale amid the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Most mining companies we work with today have succession planning practices in place with active Board involvement and an eye on high-performing talent. This was not necessarily the case pre-GFC, when companies hired and fired “heavy hitters” who were often external hires in pursuit of growth. Succession planning was not necessarily a priority at that time, and the industry employed a cycle mentality to people decisions. Post-GFC, we have seen a distinct shift in the industry toward a more robust and pragmatic approach to CEO succession planning. Mining CEOs appointed during 2010-2019 are relatively older, with nearly four out of five CEOs appointed internally – perceived as a safe pair of hands who will have accumulated a body of knowledge over a long span of time, much of which is specific to the company.

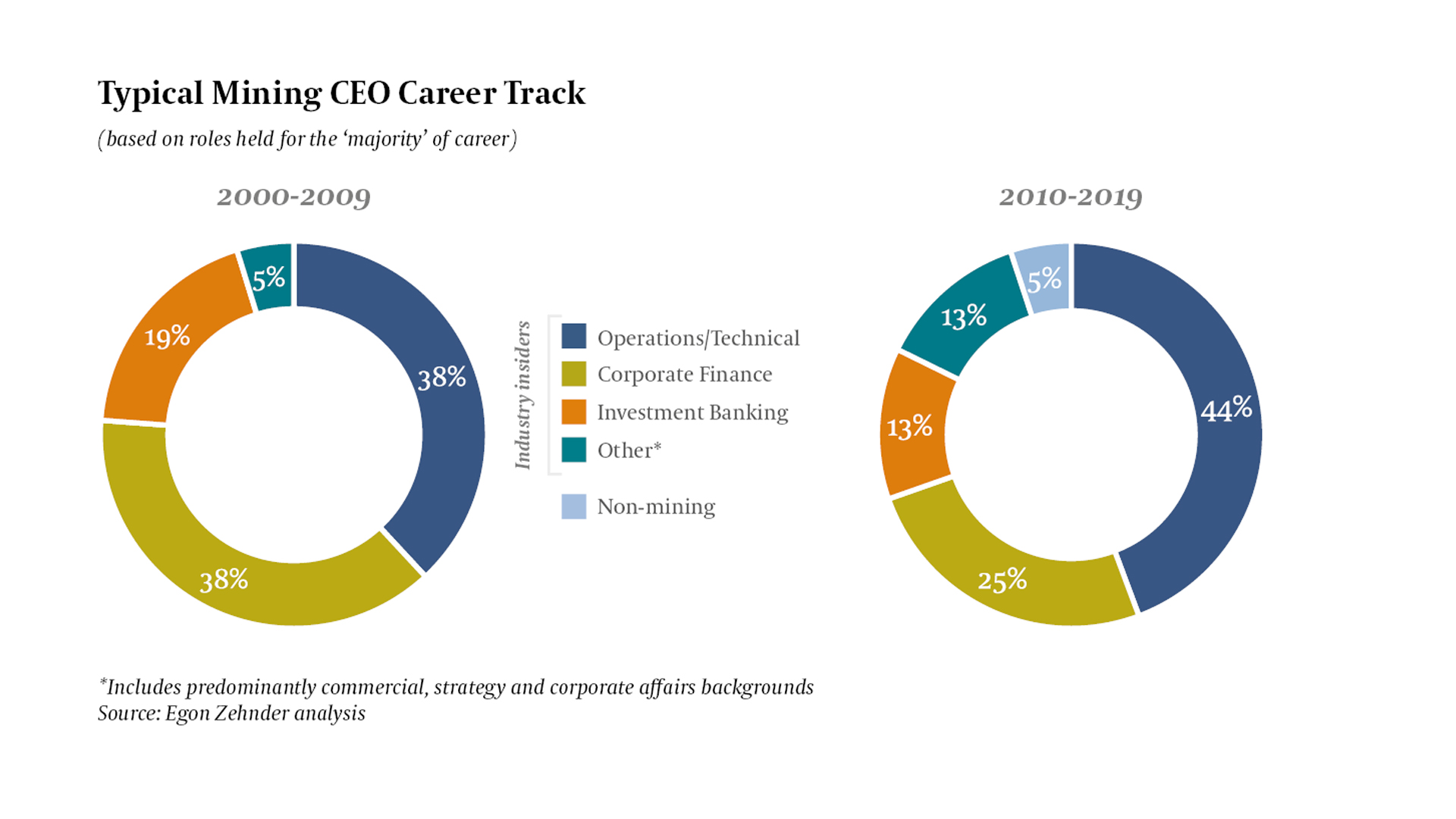

Our analysis of CEO transitions also revealed a shift in the typical CEO backgrounds between the two decades. During the growth super-cycle, CEOs with “mining focused” experience in corporate finance and investment banking comprised nearly 60 percent of all CEO hires – in particular to pursue in-organic growth opportunities characterized by mega deals and consolidation. Relatively fewer CEOs with finance backgrounds took the reins during 2010-2019, as companies prioritized productivity improvements and optimization of operating costs. The industry’s flight to safety post-GFC led to a higher percentage of CEO appointments with solid operational experience, and in most cases, intimate knowledge of company assets.

Strong succession planning limits the possibility of ineffective CEO hires, who will remain in the role longer than they should or necessitate an unplanned replacement. A positive indicator that supports this view is the percentage of CEOs replaced, which has nearly halved during 2010-2019, notably from among a larger number of internally appointed CEOs. Succession planning can also increase diversity in senior management through carefully crafted development opportunities – for example, roles that increase international exposure or P&L responsibility given to high-potential functional leaders.

How can Boards ensure a strong pipeline of potential CEO successors, ideally to promote from within? Egon Zehnder’s study, “Turning Potential into Success – The Missing Link in Leadership Development,” suggests that 72 percent of managers have what it takes to grow into C-suite roles. Strong future leaders can be developed successfully from within, but they have to be identified early on and given exposure to opportunities that will stretch and grow them. Boards can bridge the gap between raw talent and executive success by ensuring that management follows these four steps:

- Determine the most important competencies for leadership roles in your organization.

- Assess employees’ potential by looking at the five predictors associated with success – motivation, curiosity, insight, engagement and determination.

- Map people’s potential to the competencies required in various roles.

- Give emerging leaders the opportunities, coaching, and support they need to strengthen critical competencies.

Both the Board and high-potential leaders will need to find a balance between meeting short-term expectations and long-term investment in order for talent to grow from within. However, a lot can be achieved in a decade.

Developing Transformational CEO Successors

As the industry enters a new phase, we must accept that our environment will continue to be extraordinarily volatile, and our choice of leadership becomes more critical. Triggered by the COVID-19 crisis, many mining companies want to enhance the pragmatic approach they had adopted for CEO succession post-GFC. This renewed focus is an opportunity for companies to take a dynamic approach toward succession planning that remains both realistic and systematic in practice.

What we’re seeing is that succession planning as the industry today knows it (9-box grids, 360-degree feedback, etc.) is necessary but not enough. While companies have become more adept at identifying and nurturing highly capable talent, they must also recognize and cultivate future leadership potential. COVID-19 is already changing how the world works, affecting global supply chains, the workforce, and the workplace. Concurrently, there is a spotlight on business resilience, with a focus on ESG, digitalization, and commodities of the future (driven by clean energy and battery storage mega trends). The industry’s approach to CEO succession must evolve from appointing a safe and capable leader to developing a strong pipeline of executives who can embrace disruptive change and drive transformation.

Companies can cultivate transformational leadership by using a five-part model to spotlight strengths that future leaders can build on and gaps they need to address. The five dimensions are:

- Mastering complexity – the ability to sift and integrate the multiple factors influencing the company’s success, and see through the “noise” to distill real insight and set clear direction

- Orchestrating creativity – the capacity to instill a mindset and a framework for action that enables the organization to generate – and implement – truly innovative ideas

- Growing emotional commitment – the ability to create a compelling “call for action” imbued with higher meaning and strong emotional content, so building organizational commitment far beyond “programs and processes”

- Anchoring in society – the ability to connect the company’s business purpose to a long-term mandate of creating social value, and to align the organization’s activities and communication with that purpose

- Building next-level leadership – the capacity to energize and develop the next generation of leaders, using innovative models for collective action

With disruptions on the horizon, companies must be ready to meet unforeseen challenges, plan for the unknown, and prepare for what’s next. To do so, they will need to cultivate leaders who are proactive, adaptive, and innovative – and who can mobilize organizations not just to change but also to transform.