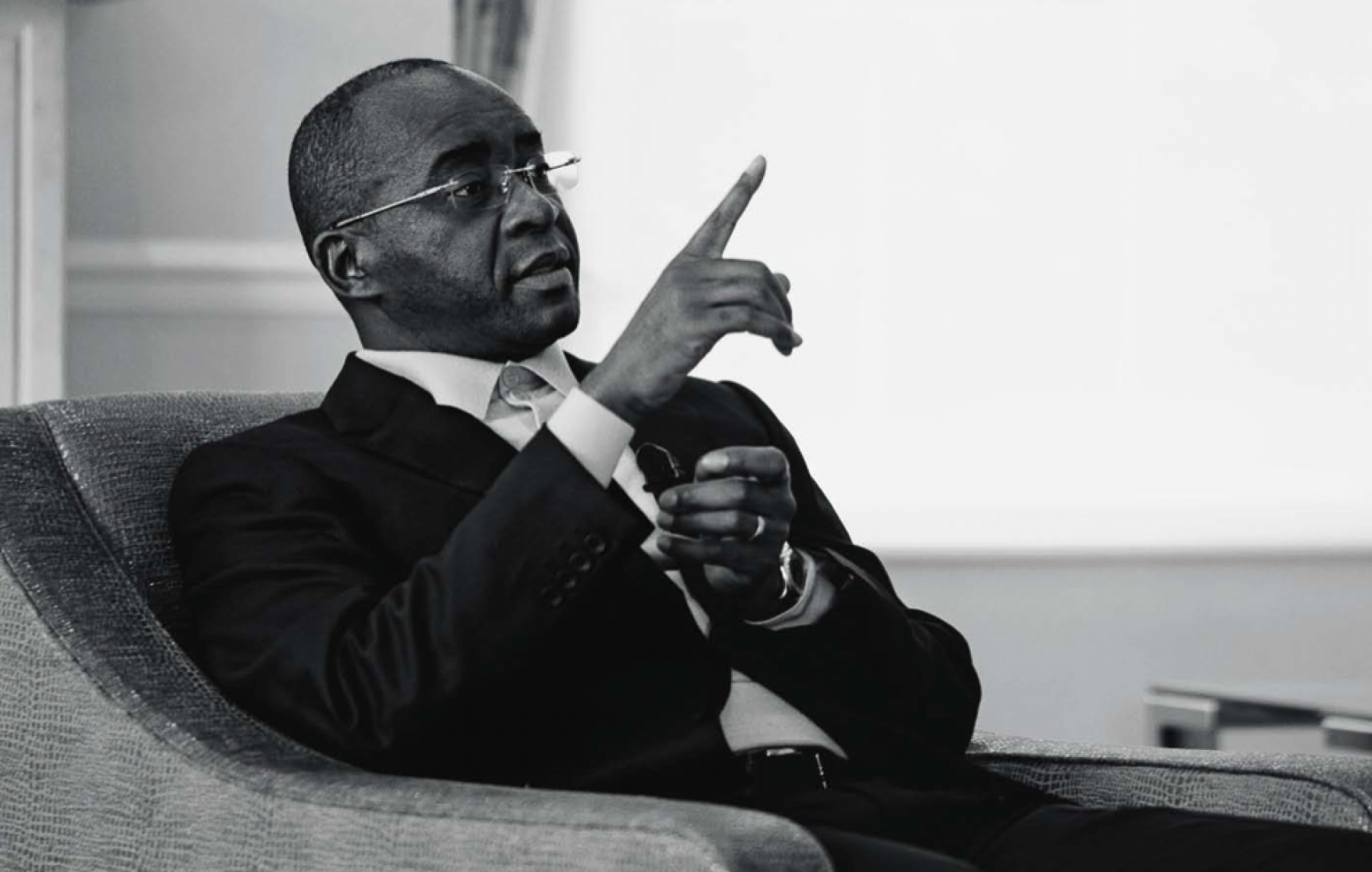

As a global business leader, African philanthropist, anti-corruption activist, and mentor to thousands, Strive Masiyiwa is a vibrant example of someone who has little doubt about what motivates him, what he hopes to accomplish, and what sort of example he wants to set for others along the way. His is a character forged by struggle and perseverance against corruption, and shaped by a deep faith that guides him on the world stage as he looks to bring about positive change to his home continent. Egon Zehnder's Xavier Leroy had the pleasure of speaking with Masiyiwa in London during a brief pause in a schedule bursting with business and philanthropy interests.

Xavier Leroyr: You recently suggested that people should stop considering Africa as “exotic” and see it more as a place for doing business …

Strive Masiyiwa: Africa is indeed open for investment. This does not mean we don’t need aid in other things. But when you come to Africa to do business, it makes sense to evaluate the opportunity in the same way you would evaluate an investment in Asia, or an investment in Latin America or Europe. That is what we do as a company.

On the other hand, there are some very real challenges in Africa. Is doing business in Africa about turning these problems into opportunities?

There are challenges everywhere, Africa included. And keep in mind that Africa is composed of 54 sovereign nations. Yes, we have the challenge of Ebola. But not in the whole of Africa; it is a problem in three very small African countries. So Africa has its challenges, but it is not a country; it is a continent. Africa has the same contrasts, it has the same challenges as any other continent, and if you go there knowledgably, do your homework, do your work, you can mitigate risks – and you can find opportunities. As a serious businessperson looking to enter the market in Africa, you have to know the differences in identity between South Africa and Nigeria, between Egypt and Morocco. Otherwise, you’re going to get yourself into big trouble.

Clearly Econet has a major advantage there. Given the global scale of your operations, would you still describe Econet as an African company?

For sure. We are very much an African company with a global perspective, much like Apple is an American company with a global outlook. We look at the opportunities globally, but we have very specific knowledge of the African continent, and we take advantage of that.

How have your African roots shaped your mission and philosophy as an entrepreneur?

I come from telecommunications, which is my core interest and my core business. So I was very fortunate that my skills and knowledge of the industry coincided with the revolution in the technology, and we were able to do some pretty spectacular things as an industry, which I think others will find difficult to duplicate. When I entered this industry back in 1993, the vast majority of the African population – 70 percent or more – had never heard a telephone ring. Today, 70 percent of Africans own a phone. That is a revolution. So as an entrepreneur, my philosophy has always been about reaching out to meet the needs of people. What do people need, and how we can respond to those needs? From there, everything takes care of itself. And I make a distinction between what people want and what people need. It is great when you can give them what they not only want but also need, because someone may want a piece of jewelry, but they may not need it. At this stage, I am more inclined to respond to needs.

What innovations are coming out of Africa that are also relevant on a global level?

In Africa, a company such as ours often has to innovate out of necessity. As we have to do things from scratch, we have managed to leapfrog traditional technologies. In general, African companies demonstrate far greater adaptability to technological change than companies in some developed markets. Consequently, you will see companies come out of Africa that will be world champions thanks to this practical approach to innovation.

As an African, do you feel leaders in the private sector there have specific responsibilities?

That is very much the case. When you do business in Africa, you must also be cognizant of the fact that Africa is a young continent. Sixty percent of the population are under the age of 30. It is a continent of young people looking for employment opportunities, looking to be inspired. This can be a dividend for the world; it can also be a major problem for the world. We are right now at that juncture where we can choose. Soon, we will not be able to choose. So those who are in leadership positions must always be aware of this.

I believe that, as a business leader, I must dedicate as much time as I can to showing young people the way, because there aren’t a lot of successful African business leaders for them to look up to – yet. It is a much greater burden for us than, say, for my colleagues in Europe, because you have had 200 years of corporate leaders that people can evaluate and look at. We have maybe fifty years by comparison, and far fewer role models from whom young people can try and learn something.

What would you say is your specific contribution to closing the leadership gap that exists in Africa?

When others look back at my business career one day, I hope they will see that I sought to emphasize the need for a boundary between business and politics – that you don’t go into politics so that you may prosper in business. Or use your business to advance politics. In my case, for example, I don’t fund political parties. I always keep a clear line. I also want people to be aware that leadership in today’s world is not just about political leadership. There are many types of leaders – business leaders, religious leaders, cultural leaders. When we recognize this, we are stronger as a society.

When too much focus is placed on the man in office, the president or the prime minister, then you have unreasonable expectations of this one person. When are we going to learn that if you do that, you’re only going to be disappointed? And I don’t think it’s only an African phenomenon. We all put too much emphasis on political leaders.

I think we’ve got to draw from a broader spectrum of leadership. Archbishop Desmond Tutu is a great moral leader, but he is not in politics. And he knows where the dividing line is. When religious leaders start declaring themselves politicians as well – that’s when we encounter problems. We need to be aware of where the dividing lines are. Otherwise people will go into business or politics with the intention of advancing the interests of their family or their tribe or region. Then we run into trouble again.

So I try to carry that message; to say that there is a place for business leaders at the table in the conversation about how we take our societies forward – but as business leaders.

You were able to get all of Africa’s major mobile operators together in one room to create an SMS campaign in response to the Ebola crisis.

Yes, and it wasn’t easy because we are fierce competitors! We organized a summit of leading business people from the African continent, meeting in Ethiopia – 37 African businesses were represented. All the mobile operators were there, and we were fired up to do some good together. Everyone pledged to give at least US $ 1 million. And so, in a half hour, we raised more than US $ 30 million.

To raise additional money, we decided to talk to all of our customers and ask them to donate via their phones. Our SMS campaign is taking place in 39 countries. This has never happened in Africa before. We have 66 African celebrities, from NBA All-Star players to soccer players, singers, and dancers, and political celebrities. They recorded messages encouraging people to make donations. It is the biggest crowd-funding campaign in African history.

This initiative – Africa Against Ebola – appears to be a new vision for African cooperation, as well as a model for leadership coming from the private sector.

The private sector is very much leading the way in response to the threat of Ebola. We now have a special foundation led by business people that funds over 1,000 healthcare workers from a dozen African countries to respond to Ebola.

Hopefully, we’ve created a template that will empower Africans, so the next time they won’t feel that they need to wait for people from the West to come and solve the problem. Yes, we still need them. But now we can partner and solve some of our own problems.

“It is amazing how organizations can adopt the persona of the leader, even when that leader is not conscious of that.”

How much would you say your company is influenced by your personality, by your identity as an entrepreneur?

Well, because I am the founder and I am still around, my identity clearly plays a role in the company. But you always want to limit that, because you want an institutional identity. A leader must set the tone on things like values. It is amazing how organizations can adopt the persona of the leader, even when that leader is not conscious of that. We’ve seen banks, even very old banks, with a new leader that is overly ambitious and cuts corners, and before you know it, the whole bank acts like a cowboy.

As a leader, you must be always conscious that you are setting a tone, that you are setting a value system. At the same time, in a multicultural environment, you are not regimenting the behavior of the other people in their personal lives, so it is a very subtle thing. But you do want to allow a persona to emerge around the organization based on values.

What do you offer the talent you want to attract?

One of the things that I have always said to our people is: When you join Econet, you join voluntarily. You join because you passionately believe that you are being led somewhere; that you are going to change something; you are going to make a difference. And our work in philanthropy, in education, in health care – it helps them to set a compass; to see that we are working towards something which makes our world a better place, and that they, too, can contribute in this way. I only spend 50 percent of my time on business. The other 50 percent, I am pursuing my philanthropic objectives. And our people know this.

Christian values seem to be of great importance for you. Did you make them part of your corporate philosophy as well?

It is my personal philosophy. You can’t make it a corporate philosophy because we have people of many faiths in our organization. However, if you live your values, other people can see whether they are good or bad. I think fundamental to what I believe is the importance of compassion. We look after more than 40,000 orphans. Everybody – our customers, our employees – know that. And if those are Christian values, then that is great.

Looking back, how important was the five-year litigation process you went through to get the telephone license in Zimbabwe? How important was it for the DNA of your company and the confidence of the people working for you?

It was extremely important, because one of the core things that came out of that was that everybody knew I was fighting a battle against corruption. I could have solved that problem in one day by just agreeing to say, “Okay, I can accommodate this, I can accommodate that,” and it would have been over. And the people knew that. But I stuck it out. I went through the courts and fought the battle. It said to people, “Hey, you can stand up for what is right. You can say no to corruption.” Africa needed to hear this message very loud – that it is possible to be in business, to do it with zero tolerance for corruption, and to be successful.

And we didn’t just fight the battle here. We fought an even tougher battle in Nigeria. It took even longer. We went through courts, arbitrations and so forth, and people could see for themselves that you could go to court in Nigeria and win. Yes, you can win! You can go to the judges. They are good judges, fair judges. There are legal systems in these countries that need to be tested. They are important to the sustainability of real business. Because if you have property, you want to know that it can be protected. You shouldn’t be expecting to have it protected by the big man in office called the president. There has to be a system; there has to be a judiciary; there has to be rule of law.

Given that corruption is still such a widespread phenomenon in Africa, isn’t it a challenge to watch over that internally as well, to make sure that nothing like that happens in your company?

Yes, it is true. Everybody must watch out for that. And it isn’t just African companies. We have seen this with big global brands around the world. There will always be ambitious people who want to cut corners. And as a leader, you must send the signal that, “Yes, there are big bonuses to be earned here if you are successful. But if you pay bribes or cut corners or do things that can hurt the brand, then you will also pay a big price.” What people don’t appreciate about corruption is this: Corruption takes two. It is not a one-sided affair. If you have said upfront, publicly: “I am opposed to corruption,” it is amazing how few people come to you asking for bribes. But if you are quiet about it and just hope they know, you will get a lot of people asking you. With me, it is amazing how over the years they have come to say: “Oh, that one! He is crazy. He’ll never pay us.” And I like that, you know? So say it loud before they come! Every corporate leader around the world should make a statement around corruption. Everybody should step up when they take over a company and say, “I am against corruption.” So, if you employ 77,000 people, let everyone know that you are against corruption. If you employ two people, let them know that you are against corruption. And remarkable as it may sound, we will get rid of it.

“What people don’t appreciate about corruption is this: Corruption takes two. It is not a one-sided affair.”

One part of your philanthropic efforts involves extensive investments in education …

When I started my business, the big crisis was another pandemic –HIV / Aids. And it was creating millions of orphans. I thought to myself, “These orphans will become child soldiers, and they will hurt us in the future if we do not educate them.” So I threw myself into the education of orphans. But orphans become adults, and we realized that amongst these youngsters, some of them were incredibly brilliant. So we began to push these youngsters to continue their studies. We have had graduates of Oxford, Cambridge, the finest universities in the world. If they want to do a PhD, then we will help them fund these studies.

We are also focusing more on skills training. We have a whole program to teach young Africans coding, so that maybe some of them will create the next Alibaba or the next Apple. We are also developing online training programs for primary and high-school students so that they can train using smartphones and SMSplatforms, so we can broaden the base of education programs across the continent. And we are purchasing tablets so that an African student at a university in Lagos can have access to the same sort of material as someone at MIT or Stanford. We have started a pilot program aimed at 100,000 students in Zimbabwe, and plan to roll it out across Africa.

Africa suffers from considerable brain drain. Is that among the problems you are attempting to address – top talent leaving the country?

It is a reality of our times. The biggest export out of Africa is not diamonds or gold or platinum; it is skills. You only need to look at the remittances. There is more money being sent home by Kenyans than the Kenyan economy makes from tourism. Zimbabwe’s income from remittances is greater than from all its mineral resources. I would not be surprised if that were the case across the entire African continent. But the challenge is not in trying to stop people leaving – but in trying to create opportunities at home that enable them to stay. That is the challenge for entrepreneurs and policymakers. We’ve got to make Africa exciting and interesting. That is how we will reverse the exodus. And that is what we need to invest in – not in building walls around Europe or putting patrol boats in the Mediterranean. We’ve got to create employment opportunities in Africa itself.

“When you do business in Africa, you must also be cognizant of the fact that it is a continent of young people looking for employment.”

About Strive Masiyiwa

Strive Masiyiwa was born in Zimbabwe in 1961. He was still a child when his family fled to Zambia as the colonial-era government began to crumble and the nation descended into civil war. Masiyiwa attended university and graduate school in the UK, returning to Zimbabwe as an entrepreneur with a background in electrical engineering. With a now-legendary determination, he eventually won a telecom license that would form the basis for Econet, one of Africa’s most successful companies. Strive sits on the board of The Rockefeller Foundation and on the US Council on Foreign Relations Global Advisory Board. He has been named by Fortune Magazine as one of the World’s 50 Greatest Leaders. As one of Africa’s most prolific philanthropists, Masiyiwa supports charities that are directly responsible for 40,000 orphans at any given time in the African countries where Econet has operations.

About Econet Wireless

Econet Wireless is a privately held diversified telecommunications group offering products and services in mobile telephony, broadband, satellite, solar, and fiber optic networks, and has recently begun revolutionizing how Africans bank and pay for products with their mobile phones. Econet has operations in 17 African nations as well as in Europe, Latin America, and Asia. Strive Masiyiwa founded the company in 1993 after winning a five-year court battle against Zimbabwe’s state-owned telecommunications monopoly. This victory is seen as pivotal in the opening of the African telecommunications sector to private capital, as well as setting an important business precedent in Africa for entrepreneurs and investors alike.

PHOTOS: JØRN TOMTER