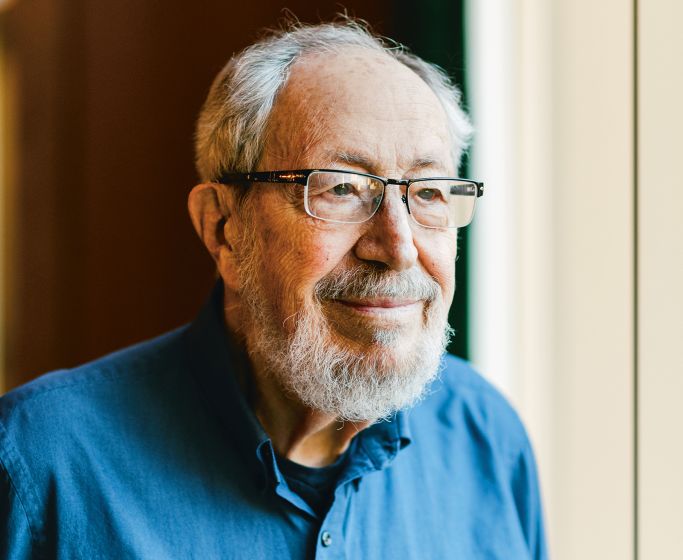

Ed Schein, MIT Professor emeritus and the father of organizational development, explains why we should forget everything we’ve been taught about leadership – and focus on getting to know each other.

In an increasingly complex world, appointed leaders simply don't know enough to decide what is new and better. Leadership is a group sport, not an individual heroic activity.

Egon Zehnder: In this complex world, what is holding back leaders who want to transform their organizations?

Ed Schein: There is no short answer, and for a reason: nobody defines what leadership is. But that is a crucial first step. If you're talking about people who have been anointed—they're presidents, they're CEOs, they're supposed to be leaders—then that's one set of answers. In my eyes, leadership is an activity in pursuit of something new and better. New and better. If I right now say we would do a better job if we moved to another room here in my home in Palo Alto, that's leadership if it works better.

So my hunch is, the biggest inhibitor is that people in leadership positions don't really know what they want to do that's new and better. They may not even have an idea. Or alternatively, their own view of what will be new and better is not based on testing with colleagues and direct reports, and proves not to be implementable at all. In an increasingly complex world, appointed leaders simply don't know enough to decide what is new and better. Leadership is a group sport, not an individual heroic activity.

Egon Zehnder: And how do effective leaders engage their people in the pursuit of something new and better?

Ed Schein: So many CEOs don't know how to ask their people what to do. They think they have to own it all. They have to be the big-shot hero, and the world expects them to be. In contrast, there are humble leaders who are appointed to fix or improve things, who take on that responsibility but are very smart about how dependent they really are on many other structures and people and processes. Being responsible does not mean for them that they have to do it alone, and they realize that they cannot implement the new and better things without the involvement of others.

Take Gary Kaplan, who changed the culture of a hospital in Seattle. He took his top people to Japan and said, "Look what they're doing over here. Do you see anything that might apply to our hospital?" He was very humble. He knew they had to fix the hospital, but he didn't know how to do that. He was also very autocratic about, "We're all going to go to Japan"; he managed the process. But the content and what they actually ended up doing, he built from the ground up.

Or Captain Marquet of the U.S. Navy, who was given a new submarine to fix because the crew had low morale. He decided that the only people who could fix this submarine were the chief petty officers who really ran it. So he collected them in a room and said, "Are you guys satisfied with how this submarine is running?" He was their captain, so they wondered: What's his game? What's his agenda? What is he doing asking us, six rungs below him? But he sat there and said, "No, I really want to know because you're the ones operating this ship. How would you improve it?"

Or what did Lee Kuan Yew have to do to create the Singapore miracle? Well, he had to have an idea of what was new and better, but then he became very humble. He built a team around himself, and he listened to the team. He created an economic development board, and they said, "We have to clean up Singapore." He couldn't do that, but he could pass laws that would force Singapore to be the kind of place where businessmen would want to come.

So, as much as he was an autocrat, he was a humble leader. He understood that, to accomplish his vision of what would be new and better would require a great many helpers that he was dependent upon, creating whole new institutions that would change how Singapore operated. He could be a political autocrat, but as a leader exhibiting leadership, he made himself totally dependent on the best and the brightest people in Singapore.

So, in contrast to many hero CEOs, these individuals were bold enough to say, "Wait a minute, I can't do that. I need help. I'm the CEO, but I need help. I need to listen to people. I need to understand how to do this from others who know better than I do."

We need to honor both what managers do to keep things moving and what leaders do who are really obsessed with improvement.

Egon Zehnder: To become this kind of leader and shape a space to co-create, what are the things that a leader needs to learn or unlearn?

Ed Schein: Our economy is shaped by the Western World, especially by the U.S., and we follow something that I call a culture of management. The managerial profession, going all the way back to Taylor and the assembly line, developed this notion of leadership that's built around setting direction. But that culture is all obsolete in the new world. So if we start with that model, we're already in trouble.

Instead, if I'm the consultant to a CEO, my question would be, "Well, what's worrying you? Do you have any problems?" He’d say, "Well, I'm supposed to set the direction for this company." Why? "Well, because my people aren't engaged enough." Oh, you have an engagement issue. Well, let's talk about that. What does the word engagement mean to you? "Well, we're having too many accidents because people aren't paying attention, and this is a difficult high-tech company." So you're having accidents. Tell me about those. "Well, we killed six people last year in a factory explosion." Well, what do you suppose went on there?

We have to have a lot of talk before the sense of direction emerges. Maybe the direction he needs to set is to create a safety program, or maybe it’s to create a new career program. But that will only come from figuring out, first of all: Who is he and what does he need to do as a manager? And then, what might be a better way to do it? Then he becomes more leaderly. But he has to figure it out in terms of the here and now: What's wrong? What's worrying him? What is the competition doing? It's very down-to-the-ground stuff, and he won't know all the answers. He’s going to have to ask a lot of people—why did that factory blow up, for example—before he even knows what he should be doing differently.

Because we have these monstrous notions of what leaders are supposed to do, all based on this old model. We need a whole new concept of what a leader does, what leadership is, and get rid of all this command and control.

And apart from that, we may be overemphasizing leadership and underemphasizing managing. Is there no room for anything staying the same? We need a term for that, and the word “managing” is a pretty good one. We want the railroad to run on time, and that requires managers, not leaders. So we need to honor both what managers do to keep things moving and what leaders do who are really obsessed with improvement. What leadership does is make it new and better.

Egon Zehnder: The kind of leader you’re talking about needs to be willing to show themselves for who they are. But people are often afraid to be that vulnerable. Why?

Ed Schein: Well, people being afraid is also the society saying, "You're supposed to be in charge. And therefore, if you don't know the answer, you're not doing your job." So naturally, the leader is going to feel afraid—he feels, “They're going to discover that I don't really know, and then they'll fire me.” But this notion that the leader ought to know is, I think, a particularly American, individualistic idea. And I'm not so sure that it isn't being bought by a lot of other societies inappropriately: because the U.S. has done a pretty good job industrializing, we must be doing everything right.

But I was very impressed when I was consulting in the late 1970s with Shell, with Ciba-Geigy, with several other European companies. They were run by boards. Yes, there was a managing director, but at Ciba-Geigy the 11 people who were an internal board really worked with each other. They all knew all the businesses. They were collectively accountable. You say “collective accountability” in the U.S., and the immediate response is, “Oh no, you've got to have a single point of accountability.”

Egon Zehnder: That’s hard to break through …

Ed Schein: It is. I'm beginning to be more and more concerned that we've built a model that smarter people don't buy into. And it may be my European background, only 10 years' worth, but I think I can see some of the pathology in our managerial culture more clearly than a lot of managers who have real blind spots on how the culture of command and control and single-point accountability create real problems.

And those managers want you to play the game with them. If you say to them, "Hey, there's another way to do things," they're not going to hire you because they want you to reinforce their model. One of the worrisome things I recently saw is an ethnography referring to a major American consulting company that is training a major Chinese company in all these classical management techniques, which is wrong. But that's what they're teaching. And that's probably what the client wants because we have a halo around all this stuff.

Egon Zehnder: So, what needs to be done to make change happen?

Ed Schein: I'd like to answer that in terms of a model of societal relationships. One of the problems of the managerial culture is that it is built on a transactional concept of how people should relate to each other. You have your role, I have my role. And we maintain a lot of distance because, if we get too close, I'll be giving you favors and it’ll be too uncomfortable. Let's stay in our boxes and in our roles.

But when we look at Gary Kaplan and Lee Kuan Yew and these other people, it’s clear that you can't get the job done that way. We have to get to know each other. We have to find out in a much more intimate way how we each work, because the job requires tight collaboration. We see that in medicine today, in the operating room. You can't have a surgeon who maintains distance from his chief nurse. They really better get to know each other.

To describe the process of getting from that role-based transaction to this more personal relationship we're coining the word personize—not personalize, but personize. Get to know each other in the work context. And that's what would have to be the first step. That manager would have to say, "I've got to get to know my people better. So I'm going to engage them a little more personally." My son-in-law doctor takes his nurse or his techs out to lunch. They build a new kind of relationship. So we call that a Level 2 relationship, or, to use another term, “professional intimacy”.

And if the potential leader doesn't see that, that he or she needs that relationship to get anything done, then nothing will happen. They'll complain, “Bureaucracy has stymied me once again.” But they reinforce the bureaucracy by maintaining distance. So the issue is: how do we get closer to each other. And that's simple. Ask a few questions. Where do you live? How do you like it here? That's how we personize, not by telling me more about your job.

It's easier to work together then, because if I ask you to tell me how things are really happening in your area, you're going to tell me the truth. Whereas if I stay distant, you're going to say, "I wonder what Ed wants to hear. And I'll tell him what will make him comfortable." So I'll be operating with blind areas.

So, personizing is the most important answer to the question of what to do.

To describe the process of getting from that role-based transaction to this more personal relationship we're coining the word personize—not personalize, but personize. Get to know each other in the work context.

Egon Zehnder: Why are so many leaders resistant to doing that?

Ed Schein: Because we've built this notion that closeness means favoritism and nepotism. We have all kinds of fears of that the closeness will interfere with the beautiful, bureaucratic, job-described world. And indeed, it will interfere. But that's exactly what you need, because the work has changed. We're not building an assembly line or a nice model factory. We're struggling with complex issues that don't resolve easily. So the nature of the work is what has forced all this. If that manager says, "Why can't I just keep going?", the world won't let you. You'll fail.

Also, people are penalized for telling the truth if it’s not the “right answer”. I was doing a lot of consulting at an electricity company, where workers had the role to stop a job when it wasn't safe from their point of view, and then some expert had to come look at it.

My colleagues and I would do focus groups with these electrical workers. They would say, "Well, my supervisor doesn't like us to stop the job too much because he has to then fill in a lot of paperwork." And I said, "Why?" Their answer: "Because headquarters wants to know, for each job stoppage, what the problem was for the valid reason that'll tell us where we need to do maintenance work." Very sound logic from the top. Get every time out recorded.

But neither the middle manager nor the supervisor wanted to do that extra work. So they started to say, "Don't stop the job all the time. What are you, a wimp?" So they undermined their own program unwittingly.

Egon Zehnder: How can executives help create the psychological safety needed for people to speak truth to power?

Ed Schein: It goes back to personizing. I think, if I want you to feel safe, I first have to build that relationship. I can't just say, as in that famous cartoon, "Tell me exactly what you think of me, even if it means I fire you." Well, that's how a lot of the executives play the game.

So I think it's relationship-building that is underneath it all. The Level 2 relationship is built over time by the subordinate learning that the boss is happy to hear about the problems and does not shoot the messenger. Psychological safety implies openness and trust which has to be built, not assumed.

But how do you get this across if a CEO doesn't sense it, if a person who's the head of a department doesn't sense it, if a manager wants to be the autocratic boss? I don't know how you get through to managers who believe that being a manager means that you can tell others what to do!

Egon Zehnder: Yes, that is difficult. What’s your advice on how can we help leaders bridge the personal and the professional?

Ed Schein: I don't have any answers other than stories, really.

For example, I had a good relationship with Ken Olsen, the founder of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). I spent 30 years working with them, and I suspect it started with something very innocent. He wanted to test me as a consultant and so had me come to his office. He was an outdoorsman and he had all these canoe paddles and stuff all around the wall. I wandered in and looked at them and asked about them, and he got all excited telling me about his summer trips into the Canadian mountains.

We never talked about work at all, but he hired me as a consultant. And for all I know, the thing I did that mattered was that I seemed to care about his canoes. That made me okay because that's where he lived his life. That wasn't a deliberate ploy on my part. It just happened.

So spotting a need, curiosity, caring, may be the operational words. But there's no formula for the level of personization, for how intimate the conversation is going to be.

I also want us to stop using the word “leader” and say “the head” or “the director”. We've got to clean up that word—just stop using it unless the person is actually leading. There are probably some CEOs who lead and some CEOs who do not. But the minute we use the word leader for all CEOs, you could say we're beginning to be very sloppy in our communication. I think this is a particularly bad problem in the business world. We like the word and begin to use it indiscriminately.

Where this comes home to roost is when you get involved with the arts and think how movies are made or how theater works. It's very hard to identify who does what kind of leading. There are the producers, the directors, the coaches, and then there are the actors. They're all leaders at some point.

Egon Zehnder: All of them following one purpose?

Ed Schein: The word and concept of “purpose” comes out of psychology. I have learned that most of what comes out of psychology is kind of useless in this human arena. I'm a psychologist, so I'm entitled to say that. But the psychologists have never learned that everything that goes on inside motivation, purpose, and so on is based on a culture, a group, a tribe—and has been socialized into its members. And the tribal rules are what matters. So purpose might be important if my tribe says you should do this. Now I've got purpose because, if I don't do it, I get the cues immediately that I'm not doing the right thing. I think of the individual as containing many layers of socialization and learning from the groups that he or she has been part of. Our strongest motivations and personality traits are the result of our group experiences, beginning with the family.

When I interviewed people in mid to late career, I discovered there are at least eight different reasons why people are in their career. You can say eight different purposes. Some wanted to be the world's best something or other. Some wanted to be captains of industry. Some wanted to be out of companies altogether because that was bureaucracy. They became teachers and consultants. Some wanted to do something significant for the world. So there were eight of these what I called “career anchors.”

And it really mattered as people got into their work life to figure out, "I can have several of these at once, but which is what I wouldn't give up? What's the anchor that really drives me?" For a lot of people like us, it's very likely the anchor and the deep value is autonomy. The reason people go into this field and why I'm a professor is because it gives us the freedom to be what we need to be.

It's a useful concept for me to know my purpose, for you to know your purpose. Is it useful as a leader should have purpose? Meaningless statement, unless you define what leadership is and what particular purpose you're talking about.

Just having purpose is human. Everyone has purpose all the time in some sense. But if I decide to become an environmentalist and dedicate my life to it, that's clearly the service anchor because it only is meaningful to me if my work solves some bigger problem. And someone else whose purpose is to make the most money in the world has a different anchor. Both working with purpose, but until you differentiate what they're each doing, that doesn't have much meaning for me.

So I talk about groups and tribes and culture and what culture makes you. You have all the cultures inside you of your upbringing. I have a little bit of Swiss, a little bit of Soviet Union, a lot of German, and then mostly U.S. Each of those countries I lived in laid down a bunch of values that are still part of me.

And so I'm a multicultural unit, but so are you. It might be more important to know how we each approach the world from our multicultural set of skills and curiosities. So let's drop all the psychological stuff and focus more on culture, ethnography, tribes, groups, how things really work. That's where it's really at. And that's where leadership is. It's in the group. When that surgeon gets into trouble and the nurse hands him the right instrument that he or she may not have asked for, that moment of leadership probably saved the patient's life, but we might not give the nurse credit for “leadership.”

Egon Zehnder: Can you can talk about the responsibility that consulting firms and leadership development firms like ours need to play in changing today’s world?

We've got to clean up the word 'leader'—just stop using it unless the person is actually leading.

Ed Schein: Your role is huge. You need to help your clients to solve their problem rather than give them a solution. And that often means backing away, saying, "We can't help you, go to somebody else." I think of Ken Olsen, the CEO of DEC. He insisted that his engineers solved the client's problem. Even if that meant they did not sell any DEC products, they must not lie to the client under any circumstance. Find out what their problem is, and if that means go buy some other company’s equipment, that's solving their problem—rather than, "I can sell you something better," when it's not really what the client needs.

And I would think that would be a horrendous problem for all of you in the consulting industry, how to stay tuned in on what the client really needs and wants. Because the problem is the client has also been brainwashed by the monetary model. So he knows that a management consultancy will give him Project X, and now he goes to your consulting company. He wants to know how you're going to be different from that one. And you're trying to establish a relationship, and he's wondering, "Why are you asking me all these questions? Where's your PowerPoint deck?"

If you ask too many questions, the client gets impatient. So sometimes, I found myself intuitively being confronting and saying, "You're working the wrong problem." And sometimes, that works much better. They appreciate the honesty. But I think it's being situationally aware and with every client building a relationship. That would be my answer. All consultants should build a relationship with whoever is sitting opposite them. Get personal. What's worrying you?

Egon Zehnder: How can consultants make the shift from having a product to sell to conducting a non-agenda conversation?

Ed Schein: Well, maybe we even need to change the concept of consulting and realize that the word “helping” might be more appropriate—because consulting already has the notion built in that you know more and that you're delivering something. But clients need help. And help can come in many forms. It can be delivery of an expert solution. It can be just reflecting, being the mirror. It can be the tough athletic coach that just trains you. But in every case, it has to be based on what the client identifies as his or her problem—so the most basic form of help is to enable the client to figure out what is the real problem. That requires the consultant to be humble and build a relationship before proposing or selling anything.

I think another problem with the consulting industry is, how do you get your own consultants to get away from billing by the hour? I heard a terrible story recently. A young woman we know was a junior at a big consulting company. She finished the day at 6pm or 6.30pm and asked her boss, who I guess was a junior partner, whether she could go home. And they were working on how to fix a big bank so that there wouldn't be new accounting scandals. But what the boss told her was, "No, you can't go home because the next two hours are billable."

Now what she's learning is that, while we're fixing the bank, we're also cheating them. The point is, her boss has a reward system that really is built on billable hours. And I don't know how you can fix that because of the monetizing of everything that supports that model. It isn't that the individual consultant is doing something wrong by delivering a product. They're part of a system, and that's what they're supposed to do in order to keep the business afloat.

Egon Zehnder: You’re advocating a different kind of relationship between the consultant and client. So, what are these relationships?

Ed Schein: A relationship exists when I can predict more or less your response to things. It is built by each of us being curious about the other, asking questions, listening carefully to the answers and, thereby “getting to know you” bit by bit. If I'm concerned about building a relationship with you, I might try to learn more about how you work. I might pick up on how your company really is different. I might want to know a little more about that. I might tell you a couple of stories about myself. And at some point, we would feel we have a more personal relationship.

I don't know how you can define it other than that I feel now I know you. If we build a relationship, it begins to be an automatic process, at least at a level that we can work together. We have personal knowledge rather than role knowledge. We find some common interest, or maybe I tell a story that suddenly gives you a new insight, or you tell me something that suddenly gives me a new insight. It's not necessarily planned. Through storytelling, we begin to get ideas, new perspectives. And maybe storytelling is the key because I think, psychologically, I have to be able to identify with you.

When I have the ability to anticipate what you'll do, that means I've now heard you talk enough that I have a sense of where you're going. And that's another way of describing a relationship, a sense of knowing where you're headed.

Egon Zehnder: That requires a lot of time, right?

Ed Schein: It requires interaction, yes, but it need not take much time. It requires curiosity and listening to each other most of all. But I have always found that this kind of relationship is worth the investment: because it will lead more quickly to a joint solution.

Egon Zehnder: Thank you, Ed Schein!

Edgar H. Schein is one of the world’s leading thinkers in organizational development. He is Professor emeritus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan School of Management. Ed’s numerous books include Organizational Culture and Leadership, Career Anchors, Humble Inquiry, and Humble Consulting. His latest book, Humble Leadership, co-authored with his son Peter A. Schein, proposes a new way of thinking about leadership based on relationships, openness and trust. Ed and Peter continue to consult with major U.S. and international organizations. An interview with Peter Schein, “It’s social!”, reflects on the ongoing challenges of digitalization and can be read on our website. And just recently a group of prominent colleagues have reviewed Ed’s thinking in »Edgar H. Schein: The Spirit of Inquiry« published by innsbruck university press.

Interview: Egon Zehnder ∙ Photos: Robert Rieger