Since 2004, Egon Zehnder has tracked gender diversity through the Global Board Diversity Analysis (GBDA), formerly the European Board Diversity Analysis. We examine trends across the boardrooms of the world’s largest companies to gain a global understanding of gender diversity. Our work explores why some countries are able to transform their boards to better represent the society around them, and reveals the continuing challenges in gaining parity in the boardroom. Our 2016 GBDA is the firm’s most comprehensive to date, evaluating board data from 1,491 public companies with market caps exceeding EUR 6bn across 44 countries.

Global Perspective

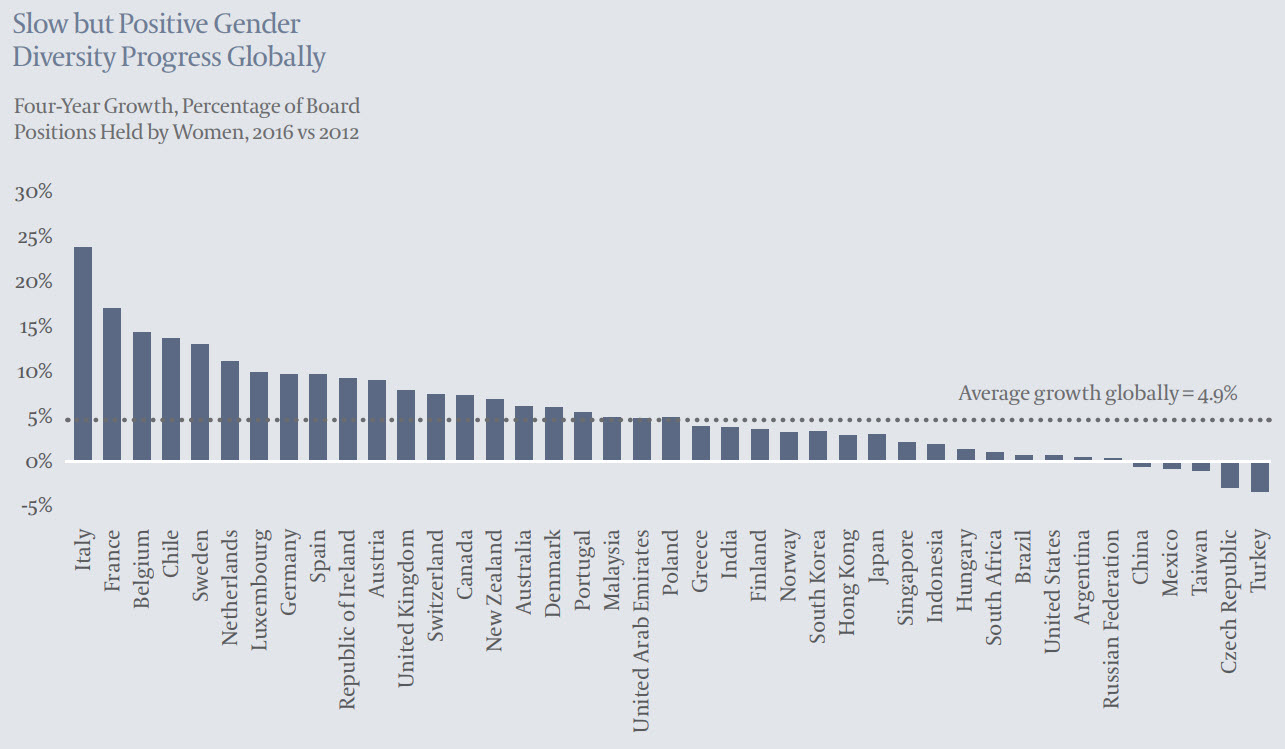

Across the globe, gender parity in the boardroom continues on an upward trajectory, with slow but positive progress – in 2016, nearly 19 percent of seats on the boards of the largest companies globally were held by women, up from about 14 percent in 2012, with 3 percent of this growth coming in just the last two years. This modest uptick is represented through a mix of positive stories in countries pioneering and championing gender diversity, as well as examples of diversity stagnation or situations where social, economic or political headwinds make it difficult to achieve gender diversity on a broader scale, let alone in the boardroom. In our 12 years of tracking board diversity, the evidence shows that diversity is most effectively manifested in those countries where gender diversity has sparked a movement through social, cultural, regulatory, leadership or political ambition, or the simple power of persuasion. The boards of some countries like Italy and France have been literally transformed: Since government-enforced quotas were passed in 2011, the share of women on the boards in Italy has increased from 8 to 32 percent, and in France from 21 to 38 percent in just four years.

Figure One: Percentage of Board Positions Held by Women, 2016 - 2012

Board Diversity Snapshot

Worldwide Diversity Gains – Positive Trends

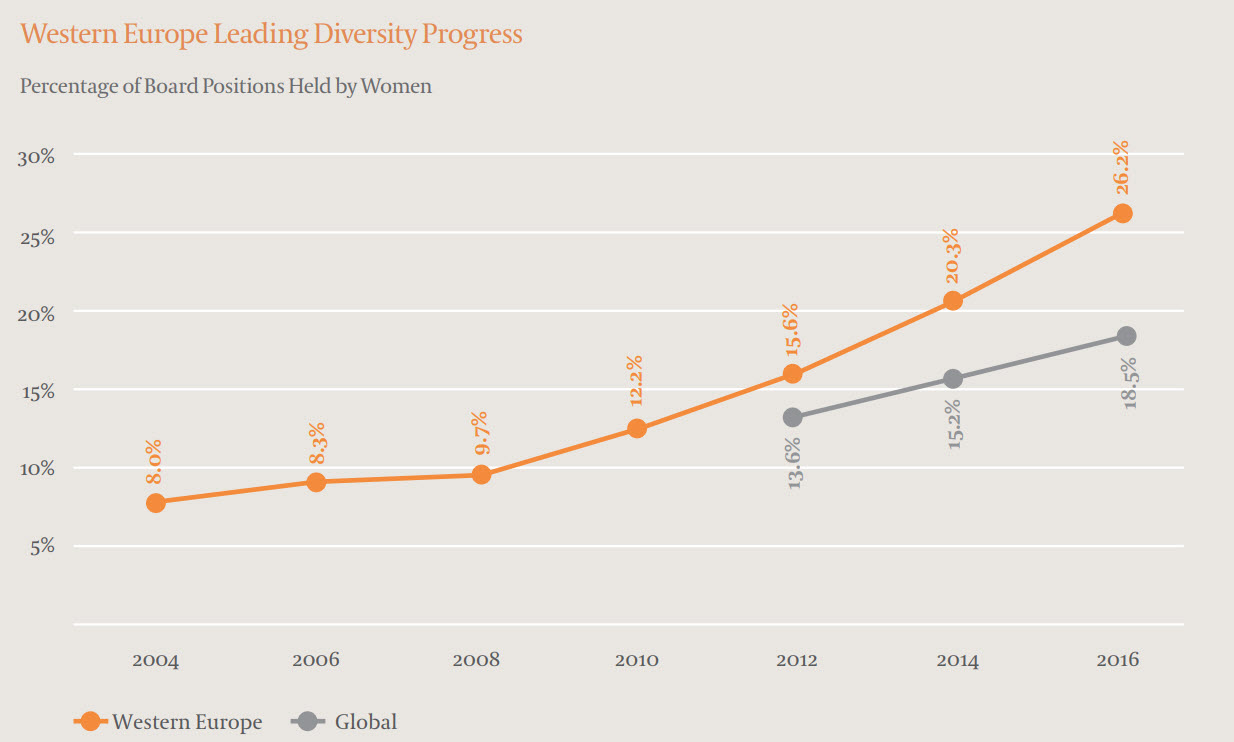

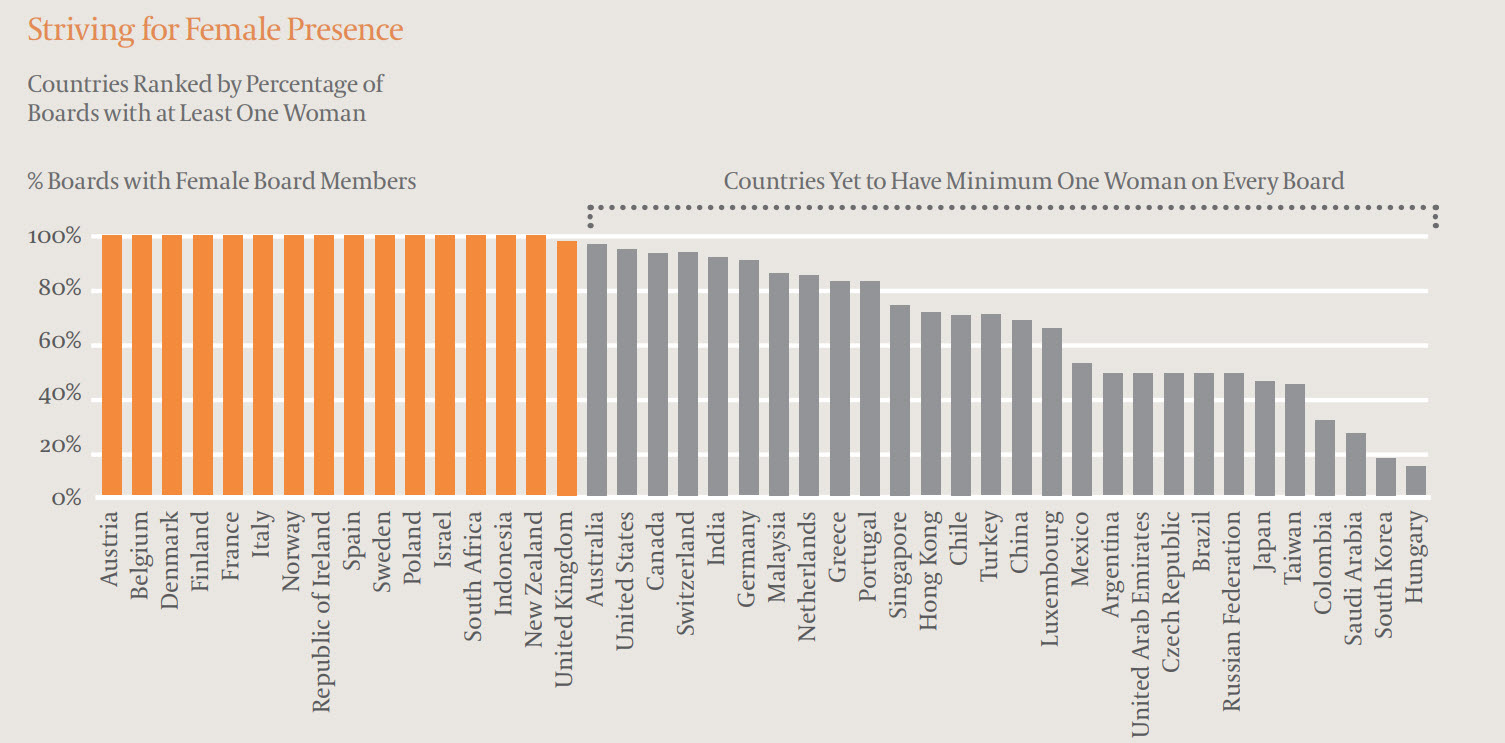

Global data from Egon Zehnder’s GBDA highlights positive momentum, as 36 of the 44 countries studied showed progress in gender diversity on boards. The same upward trajectory occurred for the percentage of boards with at least one woman, with the global overall total climbing to 84 percent compared to 76 percent in 2012. The biggest improvement in board diversity came from Western Europe. When Egon Zehnder began analyzing board diversity in Western Europe in 2004, just 8 percent of board directors were female; in 2016, 26 percent of all board directors in this region were women. Over the time period studied, Western Europe accelerated the growth of diversity gains, with a third of this growth occurring in just the last two years. Nine of the top 10 countries in terms of board diversity progress over a four-year period ending in 2016 were in Western Europe.

Figure 2: Percentage of Board Positions Held By Women, Western Europe vs. Global

Despite Momentum, Global Progress Remains Very Slow

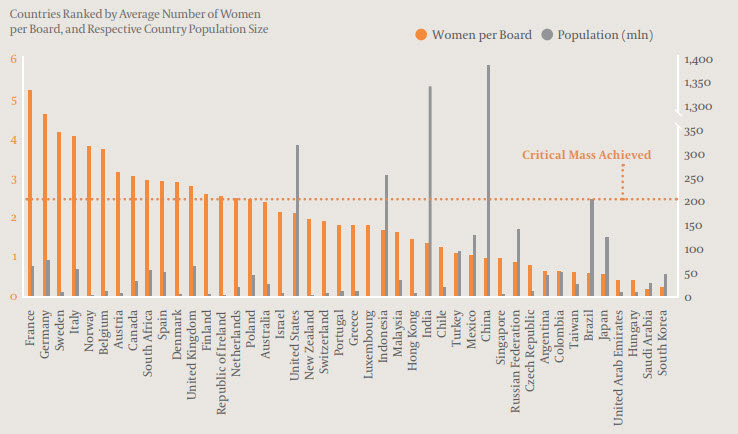

Although there have been overall gains in board diversity – and in some regions the gains have been remarkable – on the global scale progress remains very slow, aggravated by low annual turnover on boards. Egon Zehnder’s experience, supported by the highly regarded diversity research2 on Fortune 500 companies published in Harvard Business Review in 2006, shows that for gender diversity to have a meaningful impact at the board level, representation by three or more women is required to reach the tipping point for transformative and sustainable change. This means we are far from reaching this “critical mass” and ensuring diversity momentum globally. In 2016, the average board size globally was 11.5, with an average of 2.1 female members. If progress continues at the rate we’ve seen globally over the last two years (1.6 percent per annum), the average number of women per board will reach three by 2021, while gender parity remains 20 years away. Yet, it would be premature to assert success in 2021 based on average global metrics as most countries on track to achieve this target are those solely in the developed world.* A significant share of the female population is still living in countries where the diversity ambition is not yet prioritized, and these regions are decades away from reaching this critical target.

Figure 3: Women per Board on Average vs. Country Population, 2016

The U.S. is an example of a market that has fallen behind when it comes to reaching this critical mass for true diversity change, despite being an early pioneer of diversity globally. For the last four years, the U.S. has remained stagnant in board diversity progress with just 1 percent growth between 2012 and 2016, and has fallen far short of the tipping point with 2.1 women per board.

Achieving Gender Diversity Starts with Understanding the Value

While critical mass is the tipping point to achieving sustained gender diversity momentum, the benefits of having at least some diversity on boards – even single female representation – are well documented globally. According to Catalyst3 , the business benefits of diversity span four pillars: financial performance; leveraging talent; reflecting the marketplace and building reputation; and increasing innovation and group performance. In terms of financial performance, the 2016 Peterson Institute for International Economics 4 study of nearly 22,000 global companies found that those going from zero female representation at board and C-suite levels to a 30 percent female share in these positions saw a 15 percent increase in net revenue margin on average.

Figure 4: Countries Ranked by Percentage of Boards with at Least One Woman

On leveraging talent, Egon Zehnder’s experience shows that when there is a larger female presence on boards, women feel they have more of a voice and are better able to effect change:

“In boards where there were more than three women, I have found that women found it easier to raise issues, ask questions or offer insights even if the other women did not offer their support openly. Their ‘mere presence’ on the board made it easier to speak for some, not all.”

Wendy Luhabe, board member IMD Switzerland, Adjaav Dubai and the World Rugby Federation, Dublin

When it comes to reflecting the marketplace and building reputation, the Journal of Financial Economics found in 2009 that boards with even just one woman reported better attendance from all members, meaning they were more involved with higher corporate oversight. Research on UK firms from the British Journal of Management has shown that having female board directors is directly related to corporate social responsibility ratings and ultimately reputation. In China, the presence of at least one woman on the board showed many benefits from better independence of the board to a lower chance of financial restatement and improved monitoring. Lastly, diversity has been directly linked to an increase in innovation within Fortune 500 companies – with both racial and gender diversity positively affecting a board’s ability to innovate.

Countries must Prioritize Diversity to Sustain Global Progress into the Future

Despite the benefits of diversity, our global sample shows that many countries have yet to start a diversity journey, largely due to notable societal hindrances. There are still 11 countries out of the 44 studied where more than half of the boards have zero female representation, such as Japan. Thirty-four of the 44 countries, or 77 percent, have not reached the critical mass of at least three women per board, including Russia and Brazil. Moreover, there were also countries that showed negative progress – 15 went backwards during the 2012 to 2014 or 2014 to 2016 time periods, and six reported lower board diversity in 2016 than 2014, including Turkey and Hungary. The overall global ratio of male to female directors for new appointments stayed at three males to one female for board appointments. Specific country performance varies: For example, in Russia and Poland this rate is nearly eight to one, and in China it is 18 to one.

Roadmap for Building Diverse Boards of the Future

With the release of the 2016 GBDA, Egon Zehnder hopes to move beyond an understanding of the past and the present, and provide a future roadmap. This roadmap will enable everyone – from the board chairperson to committee chairs and company executives – to reimagine diversity for the long-term benefit of their organizations. Each of our recommendations draws on lessons learned from the GBDA and Egon Zehnder’s experience working with boards around the world.

1. Align Board Composition with Business Strategy

Think outside the box to shape a board that reflects the strategic vision and the company’s broader ambitions. Assemble expertise on the board that mirrors the company’s strategic objectives – global growth and expansion into new markets, customer retention, rethinking current business models to meet the needs of the technology revolution, and the like. Map board composition to meet these goals. Consider also the skills and mindsets needed for the future that don’t exist on the board today.

2. Ensure Succession Planning is Evergreen

With strategic goals aligned, taking a longer-term look to examine board turnover rates is critical. Build a bench of prospective candidates to ensure the most effective pool is considered ahead of appointment deadlines. Broaden the pipeline, and commit to having a diverse pool of candidates that incorporate a broad range of diversity – gender, skill, nationality, age and experience. New recruits shouldn’t be duplicates of departing board members; instead they should be the candidates best suited based on current and emerging strategic business needs.

3. Cast a Wider and Deeper Net for Talent

Be ready to hire people who look and think differently. Often unconscious bias can manifest itself on boards, so diversity needs to be intentional and it needs to move beyond gender. This means accepting that boards need to break from the old ways of planning – looking beyond traditionally held experience and past board tenure to focus on potential in order to create readiness for future disruptions.

4. Empower Board Leaders to be the Role Models of Inclusive Leadership

The board chairperson is the strategic visionary capable of building teams that leverage diversity for insight rather than hiring diverse board members to fill an emerging gap. It’s up to the chairperson to build a team that accepts challenges and welcomes diverse perspectives.

5. Think Beyond Tokenism

Do not simply place women in roles to meet percentage quotas or targets, but understand how diversity delivers meaningful impact at the business level.

6. Create a Tipping Point for Positive Change

Bringing the critical number of three diverse board members onto teams takes a concerted effort. Research has proven that three diverse candidates constitute the tipping point for positive change, so strive for that number but do not stop there. Incorporate goals for broadening diversity beyond gender, and lead diversity initiatives from the top.

Download the full report, Global Board Diversity Analysis 2016, to see where the world stands on board diversity: