On May 6, 2022 Egon Zehnder held a session on “Foundation and Framework to Become a Highly-Effective Member of the Board”, for board directors of India’s top public sector banks. Egon Zehnder consultants Darpan Kalra, Vineet Hemrajani, and Ashley Summerfield walked attendees through a discussion of what makes a high-performing board, and what directors and chairs should understand about their positions and how that relates to their company’s and shareholders’ success.

The discussion was broken into two segments: the “what” of a high-performing board (i.e., understanding the role of the board and its agenda) and the “how” (i.e., the dynamics of the boardroom and how it should operate via personal interactions and styles).

What Is the Role of the Board?

A board can take on many different responsibilities, but sometimes excess attention is placed on some items at the expense of valuable other ones, according to Ashley Summerfield. “What we typically find is that boards spend a little too much time on what you might call the hard stuff—the money, cash, balance sheet, margins, earnings—and probably not enough time on what is regarded as the soft stuff, like values, culture, people issues, incentives or aspects of the workforce, staff engagement, this sort of thing,” he said.

Summerfield cautioned that high-performing boards should spend more time on these “softer” items, and drew a connection to this imbalance of attention and another related to many boards’ focus on past issues. “Boards tend to look in the rear-view mirror—how was the last quarter, how was the last half year?” he said. “And actually, the real role of the board, as one of our clients summarized, is foresight more than oversight.” He likened this mindset of balance to a plane’s flying altitude: The board should be flying low enough to supervise what’s happening on the ground, but high enough to grasp the larger picture while letting management run the business.

Going from the macro view to the micro view, Vineet Hemrajani expounded on what individual board directors should understand about their role. He outlined five “hats” an effective director should be able to wear:

- Be a challenger: In a positive and constructive way, a great director will challenge what management is saying and take on the role of a “counterpoint” in order to ensure decisions are thought out strategically instead of relying on conventional wisdom.

- Take a strategic view: Hemrajani recognized that diving in the details matters, but sometimes, being able to zoom out and take a high-level view of a company is more important—something that managers too close to the ground may have trouble with.

- Understand risk: Possibly as a function of a lack of “risk orientation” by boards in the past, today, Hemrajani said that boards are too focused on risk. Yet he recognized that focus is here to stay, and directors should see evaluating risk as a pivotal part of their roles.

- Watch out for shareholders’ interests: Directors represent shareholders and should always be asking whether a company decision makes sense for them.

- Guide company culture and values: Recalling Ashley Summerfield’s advice to pay attention to the “softer” issues, Hemrajani said that directors should provide guidance on company culture, people, and values.

Ashley Summerfield added, “The only thing I would say is it’s important for the director not to be a yes man or a yes woman. Ask whether everything on your mind—all your views, all your judgements, all your sensitivities—is getting out in the room…It’s important to keep looking in the mirror before and after board meetings and say, ‘Did they really hear what I really think?’”

How Should a Board Operate?

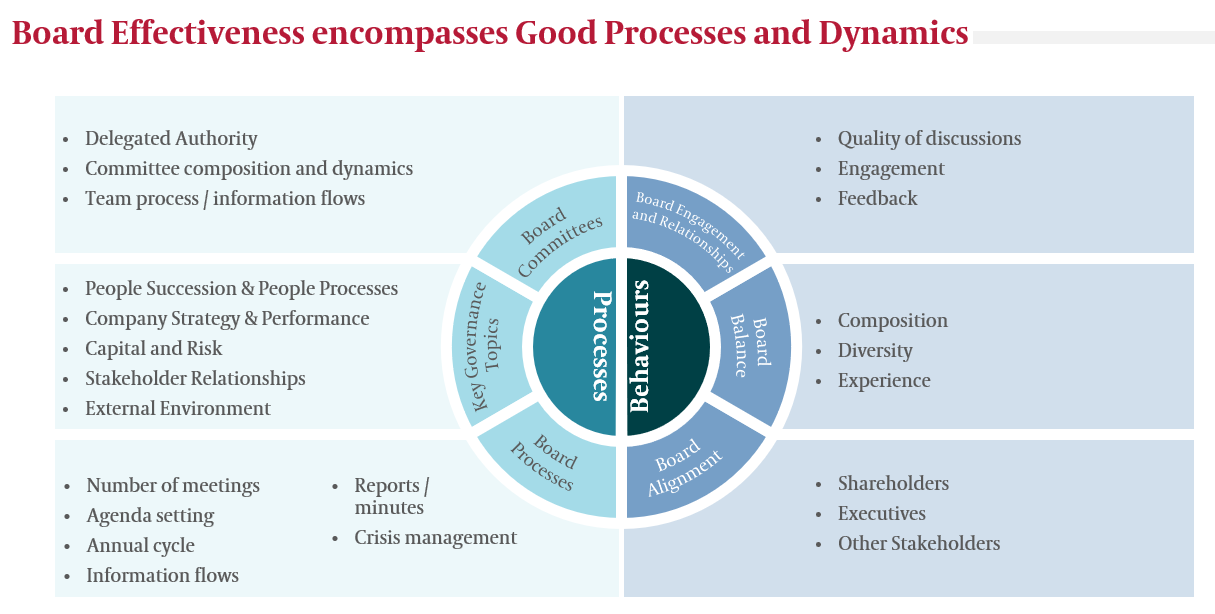

The second half of the discussion revolved around board dynamics, illuminating not just what a board or director should be doing, but how to do it.

In response to a question about directors’ issuing “dissent” against management decisions, Ashley Summerfield clarified that directors should instead approach such lines of questioning as in service to achieving a broader consensus. Effective directors should recognize that they are members of a whole, and that the best boards work as a team.

“I would try to get away from the language of dissent and more to get to the language of seeking the best answer together, which I realize means sort of tough questions,” Summerfield said. “Dissent to me sounds almost like one is trying to win a side of an argument, and I don’t think it’s as simple as that with boards. I think it’s about getting to the deeper truth of what’s going on.”

Maintaining a high quality of discussion is also vital in the boardroom. To do so, Vineet Hemrajani extolled the importance of planning the meeting far out in advance and setting an agenda up to four quarters ahead of time, while being flexible enough to incorporate new proposals as they come in. This helps with the “information flow,” and making sure the directors aren’t overwhelmed with too much material at too late of a date. A key component of this is also giving directors succinct issue summaries, so they can spend a few hours getting up to speed rather than wading through thousands of pages of documents. Ashley Summerfield added to this point:

“How many times have you read a board paper and asked yourself, what am I supposed to do with this?” said Summerfield. “And it sounds very simple, but one of the most important board processes is at the top of each paper to say what is actually being asked of the board. Is it to approve something, is to provide wisdom on something so it can be more fully cooked, is it important general background? I’ve been amazed over the years how often board papers were assembled without actually telling the board what the directors are supposed to do with it.”

These are tips for how directors should operate inside the boardroom. But what goes on outside of meetings is just as important. “The board is a board every day of the year, and you don’t have to wait for a board meeting to clarify a confusion or a misunderstanding,” said Ashley Summerfield. He continued to say that the best boards operate under a philosophy of roaming across responsibilities and areas of expertise, so important contributions aren’t silenced because directors feel like they can only speak to issues relevant to their committee, for example, or what’s discussed at formal meetings. “People often forget what happens between board meetings is easily as important as what happens at the board meeting,” he said.

What Makes a Great Board Chair?

The final area of the discussion revolved around board chairs and their specific role and ways to be more effective. Participants noted that the chair is not just a director with added responsibilities—they are leaders, architects of the board’s processes, and designers of the board culture.

First, on being an architect of the board’s processes: This is not just about chairing a meeting. In a discussion about delegating responsibilities between the board at-large and its various committees, Ashley Summerfield highlighted a chair’s critical value in enhancing this process. “A really good chair will have worked out precisely where to draw the delegated authority between committees and the whole board to get the leverage such that the precious airtime of the full board is only used for the most strategic items,” he said.

The chair’s role in board processes can take many other forms, including making balanced, focused agendas; counseling the CEO and executive team; monitoring goals and targets; and managing external stakeholders.

Board chairs aren’t just responsible for such “hard” processes—they are also lead designers of “softer” issues such as board atmosphere and culture. Chairs should present themselves as a safe outlet where management and executives can be open and transparent about issues. This also extends to directors; chairs should get to know their individual directors to understand their personalities, what’s important to them, and where they may fall in any given issue. This allows a chair to build a better atmosphere during those debates by giving directors room to speak if they may not otherwise be getting through.

Ashley Summerfield said that this can be done by maintaining personal interactions and discussions with directors outside of the boardroom. “As an example, I would expect a good chair would have private cups of tea with each director one-on-one, maybe twice a year, something like that,” he said. “Just to see the more subtle things, the mortar between the bricks, what’s actually on their mind about the company.”

Creating a culture of openness and transparency is a critical part of a chair’s role—it not only builds a better board, but as a result, a better company.