Mergers are a bold way to supercharge business growth—but they may lead to organizational anxiety. In any large-scale transformation, people may feel disoriented, which is part of human nature. What shouldn’t be normal is when leadership neglects the human risk that blending two organizations together incurs. So why do so many deals fail to reap the intended benefits, or even worse, see significant losses as a consequence? Simply put, culture can make or break a deal.

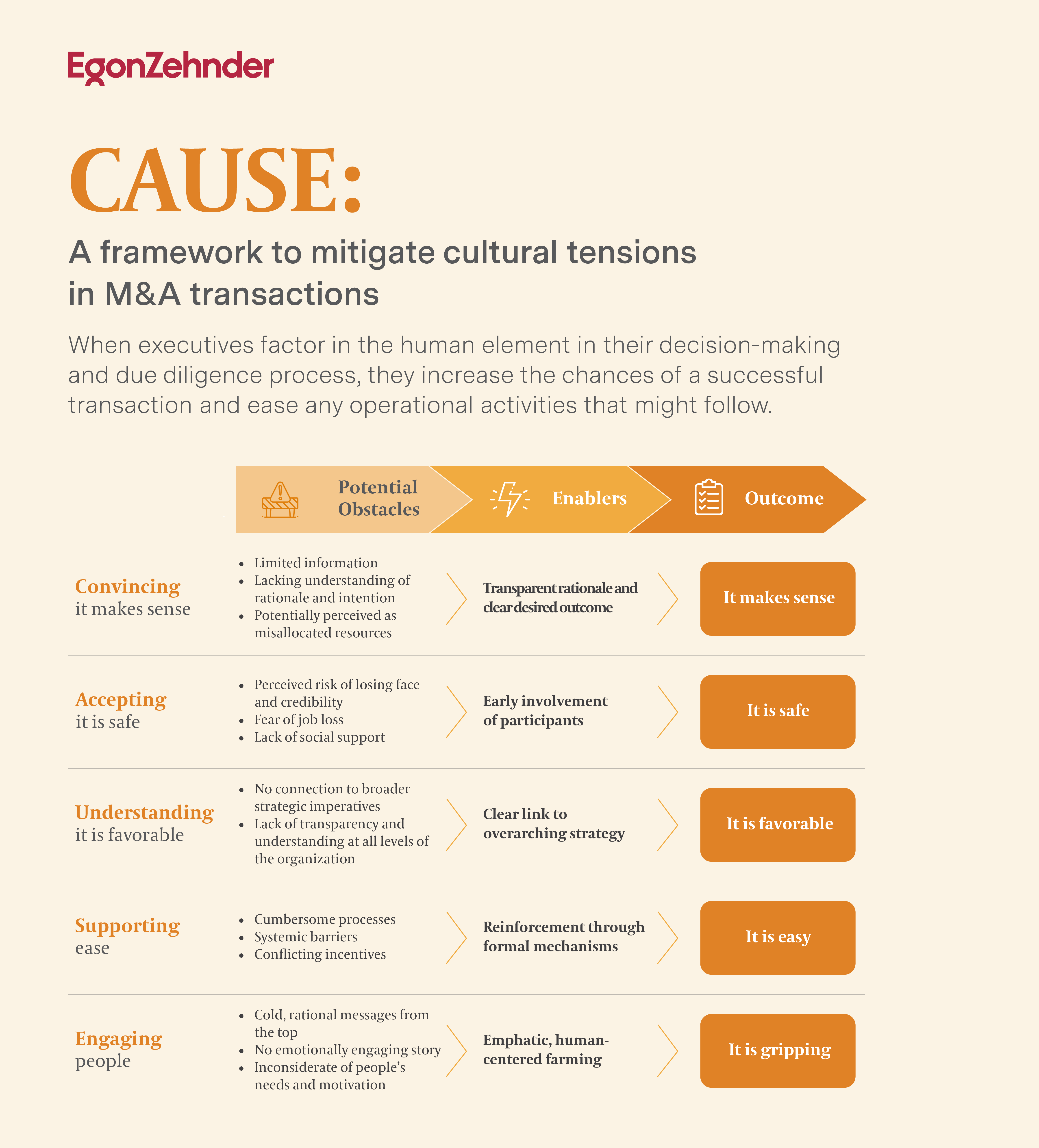

When executives factor in the human element in their decision-making and due diligence process, they increase the chances of a successful transaction and ease any operational activities that might follow.

What Could Go Wrong in a Merger?

Mergers involve radical organizational upheaval, often shaking company cultures to their foundations. And while the degree of change may vary depending on the underlying motive and type of transaction, there are four major, non-financial obstacles—although they may have financial consequences if left unaddressed—which should be scrutinized when merging companies:

- Uncertainty and Anxiety – Large-scale transformation is a significant source of uncertainty, frequently accompanied by wide-ranging anxiety among an organization’s workforce. When coping with elevated levels of uncertainty, employees assume the worst for their futures, causing work morale and engagement to plummet. Particularly, the ambiguity of job responsibilities is a neglected, yet precarious source of conflicts.

-

Identity – A solid understanding of one’s identity embodies a cornerstone of a healthy psychological mindset. Given the time spent working, individual’s occupation environment and overarching company culture typically represent a substantial part of their self-image. Yet, a merger involves one or both organizations abandoning and replacing their organizational identity with a new one, often resulting in inter-organizational conflicts. These further aggravate as people fall victim to the human tendency of forming ingroups and outgroups, unearthing our biologically inherited biases. -

Acculturation – It describes a social-psychological, anthropologically grounded process in which individuals adopt and adjust to a newly emerging culture. This phenomenon also applies during M&A activities, as one company normally attempts to impose its culture and underlying values on the other, frequently leading to a notorious cultural clash. Culture clashes originate in employees observing differences in their ways of working (e.g., different approaches to communication, leadership, and managerial supervision), sooner or later deeming their approach superior. That, in consequence, leads people to discredit and attack the other side (i.e., the outgroup), while endorsing and defending their own. -

Justice – A primary objective of mergers is to leverage assumed synergies between companies, a process that regularly involves displacing and discharging employees. However, only when people feel treated fairly, will they exhibit positive attitudes and behaviors beneficial to the desired outcome, even under conditions of adversity. Therefore, during upheavals, employees pay particular attention to distributive, procedural, and interactional fairness. Researchers have thus intensely studied and convincingly documented that employees’ perceptions of how retained and terminated workers are treated during the integration period, substantially influence employee attitudes (e.g., reluctance) and behaviors (e.g., absenteeism and turnover).

In any large-scale transformation, people may feel disoriented, which is part of human nature. What shouldn’t be normal is when leadership neglects the human risk that blending two organizations together incurs.

Despite an increased focus on culture and people-related matters in predominantly finance-driven mergers, many companies report feeling overwhelmed by the magnitude of the task. AOL and Time Warner’s merger at the turn of the century is a textbook example of how financially sound intentions can turn awry when cultural risks are overlooked. While intuitively plausible from a purely financial and strategic perspective, a cultural clash in the post-merger was, in hindsight, inevitable. AOL and Time Warner represented companies with two diametrically opposed cultural profiles, operating in vastly divergent ways. Uniting and harmonizing the two antipoles proved utterly difficult, with former Time Warner CEO Dick Parsons telling the New York Times:“(…) it was beyond certainly my abilities to figure out how to blend the old media and the new media culture. They were like different species, and in fact, they were species that were inherently at war.” As so often, the path to hell is paved with good intentions.

How to Mitigate Cultural Tensions?

To ensure a successful merger and post-merger integration that mitigates the cultural tensions and associated risks described above, companies can follow the following process of reflection, representation, and realization, to preemptively address common cultural challenges seen in merger and post-merger transactions and dramatically enhance outcomes:

Reflection. Understanding the variety of personalities, cultural heritages, and sources of meaning within the merging organizations.

Comprehending the complexity of individual and shared identities, not to mention entire company cultures, is no easy feat and takes more than a sporadically orchestrated pulse survey. It takes method. As such, Charles O’Reilly's Organizational Culture Profile represents one of the most widely used and empirically validated frameworks, conclusively organizing culture into eight complementary dimensions. Running the Culture Profile with both companies before a looming transaction allows executives during the due diligence to formulate initial hypotheses regarding the compatibility of the merging entities, informing their respective negotiation and betting strategies. Integrating two companies that have vastly different value systems will be a lot more challenging than fusing firms that are quite similar. Eventually, the cultural similarity between the firms should ideally already be reflected in the financial calculations and merger strategy.

Representation. Delineating and communicating a shared identity.

Once companies have decided to merge and possess an accurate view of both organizational value systems, executives should think carefully about the desired target culture, given the overarching context and strategic imperatives11. Simply sticking, for reasons of convenience, with the culture of the larger company will likely result in reluctance and frustration in the counterpart. Yet, executives should be aware of and open to the possibility of promoting subcultures. More and more clients devise a surrounding company culture that acts as an umbrella for the rest of the organization, uniting distinct subcultures that serve different purposes. The new cultural aspiration and underlying value structure must then be communicated effectively to the wider organization, creating a compelling narrative that values the past, cherishes the present, and seeks inspiration from the future.

Realization. Progressing toward the collectively derived vision.

While the two previous steps are crucial, they merely represent hygiene factors whose completion is a necessary precondition but not sufficient in and of itself. Once the desired culture has been designed and communicated, employees must potentially adjust their internalized behaviors and gradually move toward the newly articulated vision. Changing people’s behavior, however, is notoriously difficult. Estimates suggest that the majority of large-scale change initiatives fail to meet expectations, just like most New Year’s resolutions never outlast January.

Therefore, change efforts must be comprehensive and carefully planned. Below, we outline the CAUSE framework, which comprises five dimensions that have been effective in driving behavioral change at scale while addressing all potential risk factors with our clients:

- Convincing it makes sense – One of the main barriers to change is a lacking understanding of why change is required in the first place. Communicating a clear, transparent rationale and a concrete outcome mitigates resistance and promotes rational buy-in.

-

Accepting it is safe – People do not just need to feel the absence of risk but experience safety during the transformation. Concerns such as fear of job loss or lack of social support need to be addressed and dealt responsibly and preemptively. The earlier employees are involved in the progress, the safer they feel during the change and the sooner they demonstrate individual acceptance. -

Understanding it is favorable - Without a connection to the broader strategic imperatives, change efforts might be perceived as risky, short-lived, and potentially incautious. Demonstrating the advantageousness that comes along with the merger, linking it to the overarching strategic ambition, is essential to make it appear favorable and radiate strong strategic alignment. -

Supporting ease - The ultimate objective should be to make change seem intuitive, easy, and smooth. To do so, it is necessary for formal processes and procedures to reinforce the desired behavioral change, rather than slowing it down through cumbersome systemic obstacles, or conflicting incentives. As a result, the difficulties of a challenging or rough change process can be eased by procedural support. -

Engaging people – While humans are often conceptualized as rational agents who can effectively maximize their respective utility functions, they are also emotional creatures that respond little to cold-blooded logic alone. To ensure wide-ranging support, effective communication needs to be emotionally engaging . Thus, initiatives must be accompanied by an empathic, human-centered narrative that speaks to people’s underlying needs and desires – ensuring emotional espousal.

The Power of Empathy

Specifically, uncertainty and anxiety can be prevented by reflecting on the variety of personalities in both organizations, as well as on their needs, desires and fears. Addressing those in an empathic way ensures emotional espousal, establishes trust and individual acceptance, hence protecting employees’ work morale. Representation counteracts inter-organizational identity conflict by allowing for individual differences while communicating a shared identity and value structure. Proper representation and realization also contribute to a diminished culture conflict, as employees gradually align their internalized behaviors with a shared vision and value system, rather than discrediting, defending or attacking one another. Lastly, executives can promote justice, and the perception thereof, by communicating empathically. Providing a transparent and clear rationale (rational buy-in) and linking a given course of action to overarching strategic imperative (strategic alignment) helps employees understand executive decisions and align with the new organizational culture.

Adopting an intentionally structured process to mergers is the first step in addressing looming cultural tensions, narrowing the awareness and knowledge gap by helping reflect on individual and organizational values. Such endeavors are frequently accompanied by an outside perspective, guiding the process through an unfiltered lens and continuously challenging the reflection processes as it is often difficult to properly diagnose and assist transformation from within.

Cultural integration is difficult by design. It requires deep systemic expertise, which many organizations understandably lack (e.g., adequate benchmarking) as this is not their business focus. Our hope is that the approaches and considerations offered in this article can offer initial structure and guidance to reduce the complexity that arises when integrating different organizational cultures in the context of mergers.