Few would readily associate the Military with a leadership style centered around the concepts of “kindness” and “empathy”. However, General Richard Wardlaw, a seasoned military leader with over three decades of experience, has prioritized these qualities consistently. In fact, he went a step further by establishing a military unit where kindness was stated as a core value, resulting in remarkable achievements by the personnel.

I recently had a fascinating conversation with General Wardlaw, where he shared lessons from his military career that leaders in any field can draw upon. In this new installment of our Stewardship Conversations series, General Wardlaw not only shares his journey towards sustainability but also challenges traditional perceptions of military leadership. Throughout our discussion, he advocates passionately for leading with kindness while maintaining a keen focus on fostering high-performing teams.

Explore the highlights of our conversation below.

What sparked your interest in sustainability and how has it evolved over time?

The spark was as much of a surprise to me as it was to anybody else at the time. It stems back to 2016 when I was Director of Basing Infrastructure for the Army, overseeing the 2% of the UK landmass known as the Army Estate with a yearly budget of £1 billion for facilities management. I was surprised to find that many considered the estate to be a burden, and I advocated for viewing it as an asset and opportunity, leading to the creation of Project Prometheus—a $200 million proposal for 74 solar farms across the Army Estate. I kept developing my own knowledge on sustainability, attending the Cambridge Institute of Sustainability Leadership (CISL), and continuously working to integrate Net Zero 50 ambitions into the Army's overarching strategy.

These experiences and newfound knowledge have changed my life, and it connects with that sense of purpose that I've had throughout my life which led to me joining the military. I have spent many of my 30 years of service on active duty protecting our nation in ways that only the Army can. Sustainability was a new dimension to how one serves arguably the most important challenge that our world faces today while also helping to continue to protect our nation in a very different way.

You have been “in the business” of leadership since 1991. What have been some major learnings on how to lead effectively?

- A key learning was that the only way to lead effectively as you get more senior is through others. There's a franchised leadership aspect to senior leadership which is really profound. Linked to that has been the realization that you can never communicate enough.

- The ability to distill simplicity from complexity, the capacity to reframe problems in a way that your people really understand and are energized by is also vital. You have to actively carve time out to think because leaders don’t have all the answers. I used to put a day in my diary which I would try and protect as far as possible to think and to read and to engage outside of my organization.

- Additionally, shaping those around you – not just in your organization, is fundamental. If you cannot convince stakeholders that what you are trying to do is the right thing both for them and potentially for the wider ecosystem, then you're not serving your own leadership team well.

- Finally, who you are as a person, your credibility and empathy with your immediate team is incredibly important, and this applies on whatever scale you are operating at. It's often said in the military that a good commanding officer “sets the tone” for the regiment of 800 men and women.

Can you discuss the reality of military leadership, addressing common perceptions of "command-and-control" and “superhero” leadership?

My lived reality for the last 30 years could not be further from that perception. I've got plenty of experience in Iraq and Afghanistan where if I had relied on command-and-control, I would have fundamentally failed. Command and control means you're not investing the time or effort in understanding people’s perspectives, their context and their challenges.

When it comes to a “superhero” leadership style, while acts of bravery are common in the field – which are incredibly humbling – they are not the same thing as superhero leadership. All leaders need a little bit of that resilience and determination to keep going. You're prepared to sacrifice yourself come what may. The vast majority of soldiers are not there to sacrifice themselves unnecessarily. They do want to win, they do wish to give everything in winning, but they want to do so under leadership that fundamentally cares for them and has their interests at heart. And that has always been central to my philosophy.

I find your “Letter from the Future,” relating the benefits of sustainability for a modern deployed military, fascinating. What was the inspiration for this?

The letter, envisioning operations in 2032 with widespread use of green technology, aimed to challenge conventional thinking within Defence and highlight the immense opportunities associated with sustainable technologies. It was met with initial skepticism and the perception of exemptions for Defence from such practices, because it sought to shift the narrative by emphasizing the positive impact on fighting capability. The “Letter from the Future” emerged from a desire to paint a hopeful picture and counteract a fear-driven organizational approach. The unexpected response was overwhelming, with individuals across various roles expressing eagerness to pursue the outlined opportunities. The letter went viral within Defence, garnering support from unexpected quarters, including the Chief Financial Officer and Chief Procurement Officer. This signaled a significant shift in mindset and a recognition of the transformative potential of embracing sustainable technologies.

The “Letter from the Future” is an example of “unconstrained thinking” about future scenarios. How can leaders effectively promote unconstrained thinking in others?

There is a little bit of leadership by example here, you set a tone in the organization which says, ‘It's all right to talk this way, to think this way and be this way.’ I don't underestimate the risk I was taking there at the time. To sustain that kind of cultural condition, you need organizational processes and structures which really value the bottom-up insight and regular interaction with the workforce which, akin to practices in the military, help tap into valuable perspectives. Recognizing the importance of diversity, both in terms of demographics and neurodiversity, is crucial for fostering varied thinking and ensuring leaders can benefit from insights at all levels of the organization.

Last time we spoke, you mentioned establishing a new organization with kindness as a core value. Can you share more about how this decision unfolded and its impact on operations?

Selling this idea was challenging, especially with Military colleagues being skeptical initially, but I believe kindness has a unique ability to repair and motivate. As a senior leader, you are fundamentally trying to generate a high-performing team and organization. I very early on recognized that this was a unique opportunity while creating a new organization to also equip it with a set of values that would lead to high performance.

One of the most amazing things that happened to me was that my own team, unbeknownst to me, nominated me for the Kindness and Leadership Award. That led to me becoming a judge on the panel for Kindness and Leadership, and to collaborating with Professor Lalit from Oxford, whose work underpins the four elements of high performance: respect, trust, understanding, and kindness as foundational.

What have been some successes in adopting kindness as a core value?

Launching the initiative, I asked “Can you imagine an organization where kindness is an absolute implicit lived value? Can you imagine there being bullying, harassment, and discrimination in that organization?” And of course, everyone went, “Well no, of course not.” We launched kindness as a value 18 months ago, and the people survey results for my organization were published recently. As an organization within a bigger entity, what was extraordinary is that the “people scores” across every area of my organization were at least five, if not 10 percentile points above the average. I think it has a lot to do with the fact that we spent a lot of time investing in those values and talking about the importance of those values relating to high performance. Not values for value's sake, but because that's what leads to the performance we need as an organization.

Could you reflect on some of the leadership skills that help senior leaders to navigate complexity successfully?

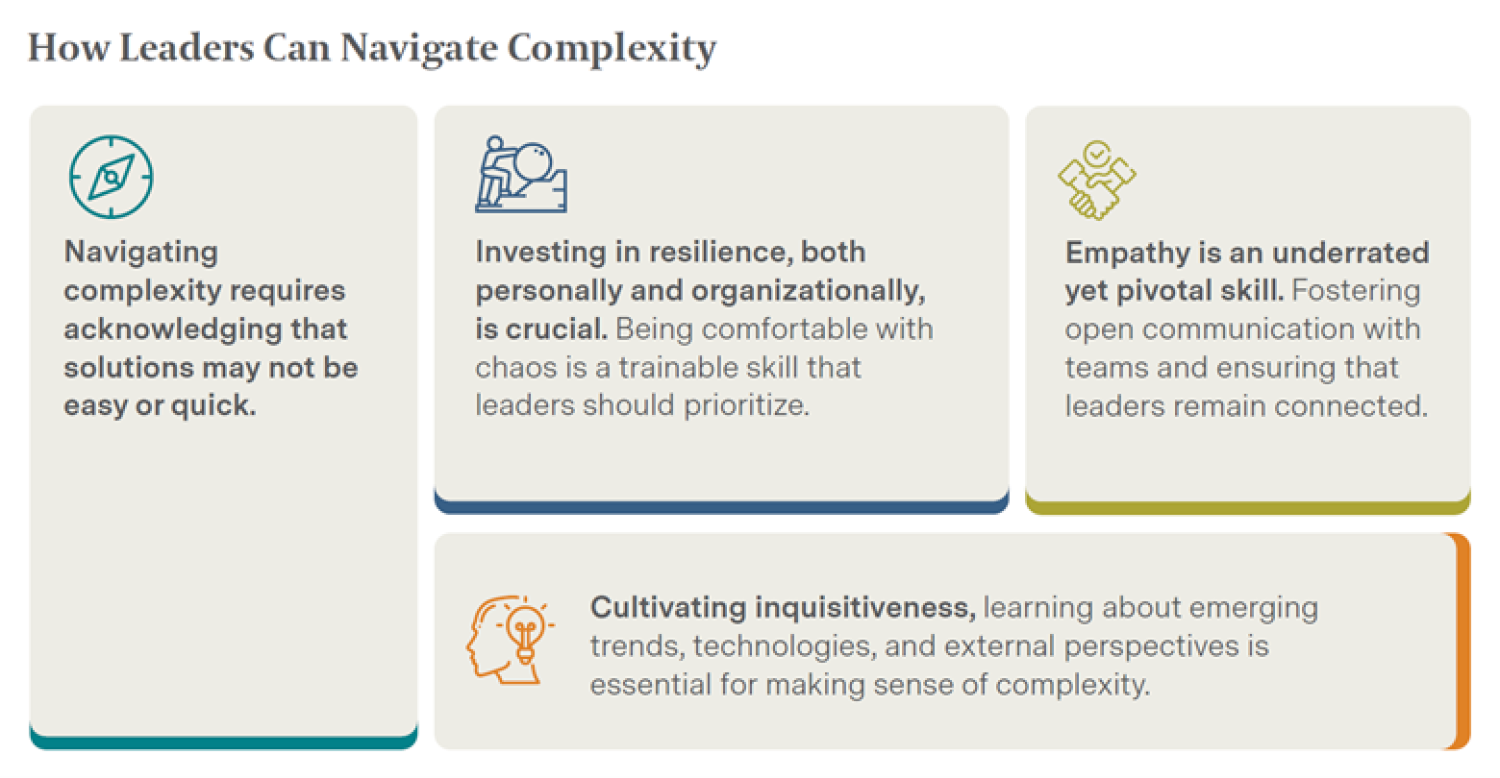

- Navigating complexity requires acknowledging that solutions may not be easy or quick. In a society driven by expectations for rapid results, leaders must recognize that certain challenges have deep-seated roots and demand time to unravel.

-

Investing in resilience, both personally and organizationally, is crucial. Drawing on military practices, the concept of mission rehearsal training demonstrates the value of exposing individuals to extreme duress, fostering resilience and preparing them to face the unfamiliar without succumbing to shock. As seen in the military's response to the COVID crisis, being comfortable with chaos is a trainable skill that leaders should prioritize. -

Alongside resilience, cultivating inquisitiveness by constantly learning about emerging trends, technologies, and external perspectives is essential for making sense of complexity. -

Finally, empathy emerges as an underrated yet pivotal skill, fostering open communication with teams and ensuring that leaders remain connected with those at the forefront of challenges.

Engaging in a conversation with General Richard proved to be enlightening. I found his perspective on the Military's role both in safeguarding the nation and simultaneously addressing the critical issue of climate change to be a fascinating combination of geopolitical, environmental and cultural considerations across multiple time horizons– reflecting the complexity leaders face today.

I was fascinated and surprised by General Wardlaw's mindset, emphasizing that effective leadership is characterized by kindness, care, and empathy. I reflected that although corporates may not necessarily operate in life-or-death scenarios, they are still aspiring to high-performing teams and organizations to deliver on their objectives. The General’s comments illustrate that genuine leadership brings together purpose and performance with kindness as an underpinning value. For some, the overt naming and practice of kindness in the workplace may be at odds with their sense of leadership identity – it may take some getting used to. I am going to use this conversation as an invitation to adopt kindness in my leadership toolkit – perhaps you can too.