View The 2018 Global Board Diversity Tracker: Who's Really On Board? Highlights and Explore the Data.

We have tracked gender and international diversity on boards around the world for the past 14 years. With the release of our 2018 report, Global Board Diversity Tracker: Who’s Really on Board?, we mark our most comprehensive effort yet.

Our conclusion is simple: Boardroom diversity matters because it leads to better corporate outcomes. Yet for all of the attention given to the topic, improvement remains incremental — and that is unacceptable. To make a difference, boards must abandon tokenism and hire a critical mass of at least three women. That approach must be directed and supported from the very top.

Our work also looks at just who serves on these boards, examining who serves in leadership positions, where new directors come from, and how board leaders create productive teams. We also highlight success stories of companies that have made board diversity a priority. At the end of the report, we offer our perspective on how best to jump-start the process of diversifying your board.

We hope this report inspires you to act — and to reap the benefits that will result.

“Companies have come to the realization that in this time of disruption and change, the ‘traditional’ perspective on governance is no longer sufficient. New voices are needed — and many of those are women.”

Jill Ader, Chairwoman, Egon Zehnder

One is Only the Start

Overall, there is certainly some good news to share: Since 2004, when we first began to track board diversity, the overall presence of women and international directors has grown significantly.

In 2018, 84.9 percent of large company boards across 44 countries included at least one woman among their directors. Overall, 20.4 percent of all directors in the countries we studied are women — up from 13.6 percent six years ago. In Western Europe, board positions held by women have risen from 15.6 percent to 29.0 percent over the same time period. On the international diversity front, 72 percent of the companies surveyed had at least one non-national board member.

In 19 of the 44 countries we studied, all of the large-cap companies have at least one female director. This “One on Board Club,” up from 15 countries in 2016 and just eight in 2012, includes nine countries that have instituted a quota, a law requiring that companies reach a certain percentage of women on boards by a specified date.

The progress, however, is far from consistent, as 15 percent of large-cap companies still have no women on their boards. 25 countries, including China, Brazil, and Russia, are home to large companies with no women on their boards at all. And in the past two years, the overall percentage of companies with at least one woman on the board has stayed roughly flat.

Inconsistent Progress: Champions, Slow Movers, and Underachievers

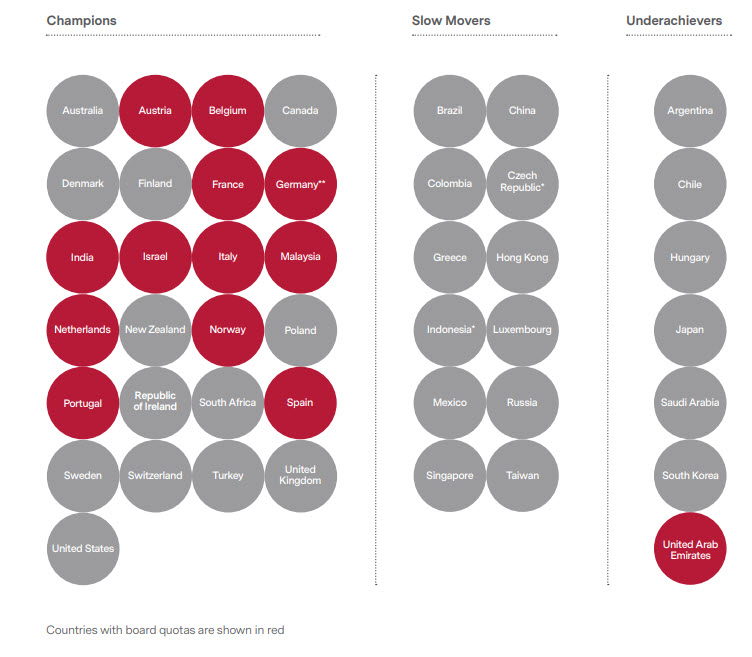

Looking at several factors, including the numbers of new female board appointments and how many women on average sit on a board, we have classified the 44 countries into three groups: Champions, Slow Movers, and Underachievers.

In the “Champions” category, we see countries that are making significant progress on board diversity. This may be driven by a good dose of public, shareholder and stakeholder pressure as well as regulation. It has also been a result of increasing numbers of women reaching the upper echelons of business.

Yet in some countries that have historically been Champions, progress is slowing: For example, although the United States has long been considered a diversity leader, overall progress in adding women to the boards of large companies has slowed; the percentage of female directors has risen by just 3.2 percent since 2012.

Look at some other countries in the “Slow Movers” group, and optimism continues to dim. The 12 companies in this list include Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, and Singapore. Here change is happening, but at a relatively glacial place; on average, just 10 percent of new board appointments are women.

In our “Underachievers” group of countries — a list that includes Argentina, Chile, Hungary, Japan, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and the UAE — less than 55 percent of boards of directors have at least one woman, and less than 10 percent have two or more. But even in these countries, some companies are leading the way with new practices and differentiated results.

*Criteria for the classification of countries

| Champions | Slow Movers | Underachievers |

| Criterion 1: >=60% of boards with at least 1 woman on board | Criterion 1: >40% and <=75% of boards with at least 1 woman on board | Criterion 1: <=55% with at least 1 woman on board |

| Criterion 2: >=18% female new hires | Criterion 2: >10% female new hires | Criterion 2: <10% female new hires |

| Criterion 3: >=30% of boards with at least 2 or 3 women on board | Criterion 3: >=5% of boards with at least 2 or >=5% and <30% of boards with at least 3 women on board | Criterion 3: <=10% of boards with at least 2 or 3 women on board |

Success Stories

Inconsistent Progress: Our Take

The relative lack of women in top business roles presents a pipeline challenge for directors, one that is both created and exacerbated by lasting cultural norms. And yet that is no excuse for not making the effort to find qualified female directors, difficult as it may be.

Even in countries where senior women leaders are rare, some innovative companies have established new talent networks rather than relying on existing ones. Says Egon Zehnder Chairwoman Jill Ader: “Companies have come to the realization that in this time of dramatic technological change, the ‘traditional’ perspective on governance is no longer sufficient. New voices are needed — and many of those are women.”

Tokenism to True Impact: The Magic of Three

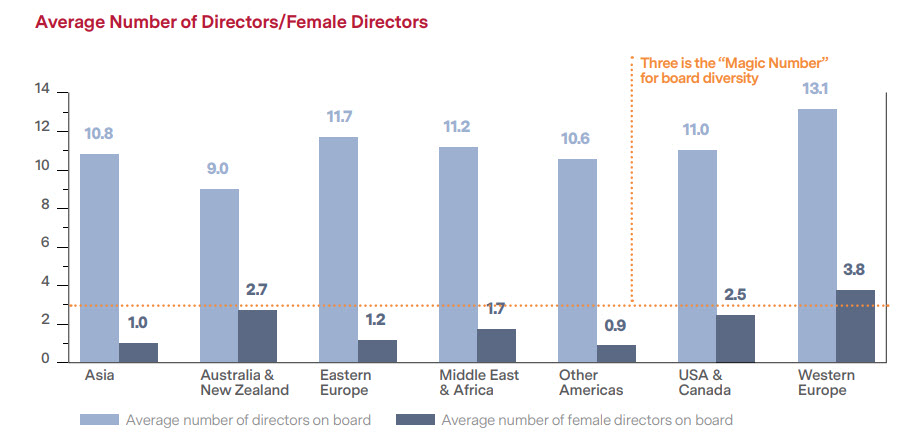

Having one woman on a board is progress. But it is far from a gold standard when most boards average between nine and 13 members, and some have as many as 20.

There is significant evidence suggesting that it takes at least three women on a board to fully reap the benefits of gender diversity. One MSCI study found that companies with at least three women on the board in 2011 experienced a median increase in return on equity of 10 percentage points and earnings per share of 37 percent by 2016.2 This “critical mass” changes both the way the board is run and the way women are able to share their insights. Says one chairman of a large financial firm in the United Kingdom: “My conclusion is that having one woman on the board doesn’t work; having two is a bit of a cabal, but when you get to three, it all changes. On average, women have much greater EQ. In my experience, they enhance the ability of the board to see around corners and scan the horizon.” Let’s take a closer look at the average number of women on a board by country.

First, the leaders: Australia, Belgium, Finland, France, Italy, Norway, and Sweden all average more than 30 percent female directors (France leads with 42 percent). The countries with the lowest percentage of women on board are Hungary, Japan, South Korea, and UAE. None of these countries average more than 6 percent women; for Saudi Arabia, the number is 1 percent.

If we delve further into the numbers, we see 13 countries that have reached the magic number: Here, the largest companies have, on average, three or more women per board, with five countries (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, and Sweden) averaging four or more. All of these countries except Sweden operate under some form of quota system.

Success Stories

The Magic of Three: Our Take

Boards must raise their aspirations if they want to have true impact. Yet the fact that many large companies require their directors to be experienced directors or CEOs in order to even be considered for a board position — and that, conversely, many companies looking for CEOs want to see external board experience — means that there is a true pipeline problem. Complicating matters is the fact that many existing female CEOs already serve on several boards, making it difficult to add new board work.

To address this issue, boards must be willing to develop first-time directors. “We need a new definition of board-ready,” says Cynthia Soledad, the Co-leader of Egon Zehnder’s Diversity Council. “It is being open to candidates who do not have prior board experience, but have sufficient executive experience to be additive to the board.”

An executive with functional or industry experience and high executive leadership potential can add value, whether or not she is a sitting CEO or director today. This executive potential is made up of four traits: curiosity, insight, determination, and engagement. Our experience shows that individuals with these traits can step into new situations and deliver impact.

Boards who are willing to go beyond their known networks to really investigate and evaluate the executive talent pool and connect with high potentials can fill the pipeline. Says Christina Gold, a member of three boards, including ITT and New York Life: “This is not a one-time event: It’s about constantly nurturing relationships over a couple of years.”

“We need a new definition of board-ready. It is being open to candidates who do not have prior board experience, but have sufficient executive experience to be additive to the board.”

Cynthia Soledad, Egon Zehnder

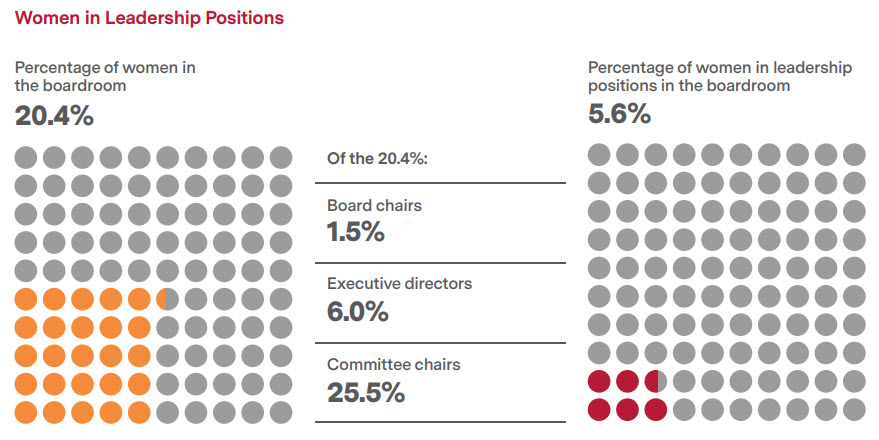

Board Leadership: The Disappointing Truth

While it is good news that women now make up 20.4 percent of directors in our study, it is equally critical to advance the number of women in leadership positions on boards. This matters not only because some board positions are more powerful than others — but also because diversity in board leadership correlates with diversity across the rest of the organization. Says Karoline Vinsrygg, Co-Leader of Egon Zehnder’s Diversity Council: “When gender diversity becomes the norm in a boardroom, we also start seeing more types of diversity, such as ethnic background, expertise, etc.”

Overall, just 5.6 percent of all board seats are held by women in leadership roles.

In the U.S. and some other countries, it is the nomination and/or governance committee that leads the selection process for the Chief Executive and other board members. A recent study published in Sloan Management Review by Deb Henretta and Kimberly Whitler shows that when women lead these committees, there are, on average, 21 percent more women on the board 3, creating a virtuous cycle.

When it comes to executive and non-executive chair roles — the true leaders of the board — the numbers are significantly worse: Just 4.5 percent of non-executive chairs in the countries we studied are women, and only 2.5 percent of executive chairs. Those numbers have actually decreased in the past two years, each falling by half a percentage point globally. And in almost half of the countries we measured, there are no women at all in board chair positions.

These numbers have implications for the entire board: A 2017 study by Deloitte found that companies with a female chair have nearly twice the amount of women serving on boards that male-chaired companies do.

Success Stories

Board Leadership: Our Take

Boards must look closely not just at placing women on the board, but also developing them for leadership positions to create sustainable diversity. Says Ashley Summerfield, leader of Egon Zehnder’s Global Board Practice: “At every stage — briefing, long lists, interviewing, selection — the Nomination Committee should repeatedly ask itself, “Could this individual — because of gender, ethnicity, career experience, thinking style — bring us valuable, fresh angles that may take us out of our comfort zone but be a service to stakeholders in the long run?” Boards must be thoughtful about the committee leadership positions new female directors could take on in the future, and purposefully train and prepare them to play these roles. In the meantime, chairs must train and educate the current (mostly male) committee leaders to fold diversity into their overall approach to governance.

“At every stage — briefing, long lists, interviewing, selection — the Nomination Committee should repeatedly ask itself, 'Could this individual — because of gender, ethnicity, career experience, thinking style — bring us valuable, fresh angles that may take us out of our comfort zone but be a service to stakeholders in the long run?'”

Ashley Summerfield, Egon Zehnder

Where are the CEOs — and How Can They Help?

It is fascinating — and concerning — that the increases in female directors have not been mirrored inside the corner office. Our data show that women make up just 3.7 percent of worldwide CEO positions in the 44 countries we tracked — and that this number has not changed over the past two years. Even more surprising is the fact that in seemingly progressive countries like Finland, Canada, and Germany, there were no female CEOs at all in the large set of companies we studied. This matters: There is, in fact, a correlation between diverse CEOs and diverse boards of directors, though it’s not quite clear which drives which.

Success Stories

- Unilever, United Kingdom and Netherlands: Accountability in the Corner Office

- Ørsted, Denmark: Balancing Diversity and Efficiency

Where are the CEOs: Our Take

Change must come from the top. Without the full and active support of a Chair and/or CEO who make clear that board diversity is a strategic imperative rather than a “nice-to-have,” unconscious bias in the succession planning systems won’t be uncovered and addressed. But if those leaders put their reputations and energy behind the establishment of new practices, the way new director candidates are screened, assessed, and chosen will shift almost immediately. Says Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever: “It really has to be done with conviction by the CEO of that company.”

“The pressure goes up on a board chair to be a real leader, having assembled a diverse set of characters.”

Philip Jansen, CEO, Worldpay

Yet the Chair and CEO must do more than help appoint diverse directors. They must also onboard directors in a way that celebrates rather than diminishes different perspectives, including allowing time and space for debate. Importantly, it is equally critical to make sure that the existing board members understand just how much things may change. “The pressure goes up on a board chair to be a real leader, having assembled a diverse set of characters,” says Philip Jansen, CEO of Worldpay. Decisions that were once easy because of aligned views may be tougher, and every board member must be prepared for a messier — but ultimately richer — experience.

New Directors: The Pipe Dream of Parity

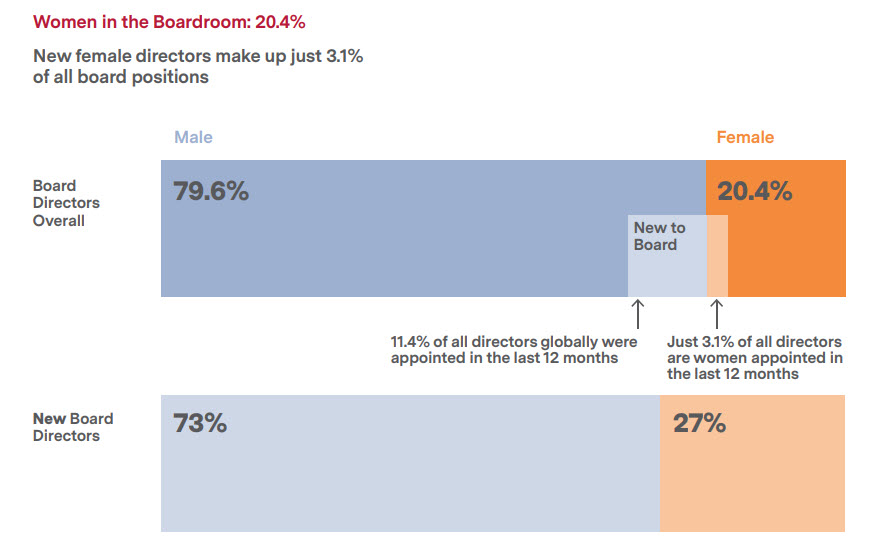

Many companies (including Egon Zehnder) have publicly pledged to achieve gender parity at various levels of corporate leadership or on boards. This is a bold and positive commitment, but one that seems impossible to achieve at the current rate of change. If there is ever going to be anything approaching parity on boards, it must come from an acceleration in the hiring of new female directors. In 2018, new board appointments — those brought on within the past 12 months — made up 11.4 percent of all board positions. Of that number, 27.0 percent were women, up from 24.1 percent in 2016.

This is a significant shift that definitely outpaces the current representation of women on boards. Yet it means that nearly threequarters of all new board positions worldwide are still going to men and that new female appointments make up just 3.1 percent of all board seats. What’s more, turnover on boards has decreased in every region, meaning that there are even fewer opportunities to appoint new and diverse directors. While the number of new directors varies dramatically by region — 35 percent in Australia, Western Europe, the U.S., and Canada versus 16.7 percent in South America and 12.5 percent in Asia — it is hard to square the reality with the lofty goals set.

Success Stories

- The Hershey Company, United States: First Skills, Then Potential

- Siemens, Germany: Diversity as a Business Imperative

New Directors: Our Take

The conclusion is simple: Without a major change to the numbers of new hires, it is mathematically impossible to get to parity — a goal many organizations aspire to.

One way to accelerate change is to refresh the board more frequently and to fill the new slots with diverse candidates. In a recent survey of U.S. board members by Deloitte, 87 percent said they supported term limits.6 And in the UK, the government has passed a law limiting the term of board chairs to a maximum of nine years in total.

Leaving the gender issue aside, the old paradigm of board members having a seat for life is less and less relevant in an environment that requires a different style of leadership — one that is proactive, not reactive, that’s flexible and open to new business models, that is digitally savvy. It is true that a board needs “corporate memory,” but this has often been overemphasized vis-à-vis “current” business experience. In today’s fast-changing business landscape, this is a liability.

Also, cultural changes and social progress have resulted in younger generations being more open to female leaders. Says Karoline Vinsrygg, Co-Leader of Egon Zehnder’s Diversity Council: “Focusing on refreshing talent with quicker turnover could add diversity of gender, age, and experience to boards.”

“Focusing on refreshing talent with quicker turnover could add diversity of gender, age, and experience to boards.”

Karoline Vinsrygg, Egon Zehnder

Quotas: Effective — to a Point

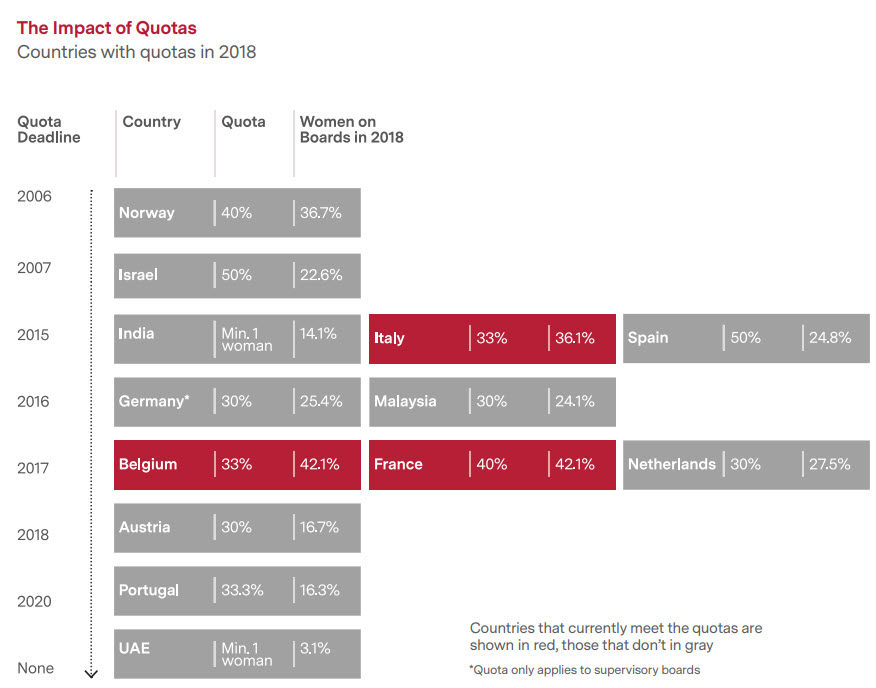

Wherever one stands on the idea of quotas, it is a fact that the most significant improvements over the last decade in board diversity have come in the countries that used regulation to get there.

The first country to impose a quota, Norway, met its target of 40 percent women on boards of public companies within two years, though it has not improved since then, and in 2018 dropped to 36.7 percent.

Some other quota countries have managed to meet their goals — some, of course, under the penalty of fines or sanctions.

Other countries have used targets instead of quotas, such as Sweden and the United Kingdom. Here, too, there has been progress, with the UK reaching 28 percent this year. The UK government also encourages search firms to report their own diversity statistics, and Egon Zehnder is proud to report that 44 percent of our placed candidates on UK-listed boards in 2017 were women.

Some countries, such as the United States, are resistant to regulatory solutions. However, in October 2018, the state of California — home to Facebook, Google, and many other technology giants — passed a law establishing quotas for boards domiciled there, with all boards required to have at least one female director by 2019 and equal representation by 2021.

Elsewhere, cultural factors mean that the available number of women in the business world is so small that the only way to meet such targets is to import female directors. This can be a double benefit in that it also boosts international diversity; on the other hand, these companies may not be investing in the development of local talent.

Quotas: Our Take

Quotas force change. Yet quotas — like many regulations — have both perceived and real unintended consequences. The first, of course, is the presumption that quotas force companies to choose unqualified women as tokens who are not taken seriously. Certainly, quotas have forced some countries to look at different résumés and competencies, given that the normal pipeline of CFOs and CEOs is not large enough to sustain the demand. But that does not seem to have had any measurable negative impact on corporate performance.

A second observation about quotas is that they seem to work until the target is reached — but then progress slows. All of this brings up a key question: Are quotas supposed to be a ceiling — or a floor? Do targets make more sense? And once a quota has been reached, what else can be done to push diversity to the next level?

International Diversity: Increasingly Important in an Interconnected World

Although most of our report focuses on gender, diversity is of course also represented through race, ethnicity, country of origin, age, and different ideological and political perspectives, or what we call diversity of thought. Incorporating all of these points of view contributes to a stronger business.

Our 2018 data show that 72 percent of the companies surveyed had at least one non-national board member — a number that has risen by two percentage points since 2016. Australia and New Zealand perform best, with 95.0 percent of boards having at least one foreign board member, and Western Europe is not far behind, at 92.5 percent. On the other side, both Asian and South American boards lag, with just 58 percent of boards having a non-national director.

Success Stories

International Diversity: Our Take

To operate globally, particularly in the current environment of geopolitical volatility, international board diversity is an imperative. Directors of different nationalities and cultures bring a different approach to business altogether and can be of tremendous help with a company’s foreign markets. They also offer alternative approaches to governance and new talent pools, particularly in countries without a lot of internal diversity. Yet making such a board effective requires thoughtful onboarding of the new directors as well as teaching existing directors that diversity changes board dynamics.

Companies must think carefully about whether their board reflects not only their employee base but also their customer base — and if they do not have the expertise they need, they should consider recruiting outside of their home country to get it.

From Talk to Action: What You Can Do Now

For all of the frustrations around the pace of change, there are reasons to be hopeful. At Egon Zehnder, we focus entirely on senior executives and board members, helping place them in companies but also helping to develop them as leaders. Our experience, combined with the above case studies of success, show that meaningful change in boardroom diversity is absolutely achievable — if it becomes a core element of a company’s overall strategy. There are several long-term and short-term actions that companies can take to make sure that their boardrooms reflect both their customers and employees.

1. Make Leadership Accountable

A focus on diversity and inclusion has to be a core part of a company’s strategy and has to come directly from the top. If board leaders and CEOs make diversity in leadership an explicit goal — one that will be rewarded if achieved or, possibly, penalized if missed — it can and will happen. But leaders must communicate its importance to the entire workforce over and over again — and prove it with action rewarding those who promote diversity — or it will not be taken seriously.

2. Raise Your Ambitions: Focus on Three

Hiring a female director simply as a token is a mistake that will not improve the effectiveness of your board. True diversity replaces groupthink with healthy debate, which leads to greater innovation and better results. And until a board reaches the critical mass of three — the number that studies show shifts the dynamic — little is likely to change. To get there, directors must be proactive about spotting female talent, including having a watch list of executives with potential. They should also consider board term limits or encourage more active turnover.

3. Set Measurable Goals

Opinions on whether to impose a diversity quota on boards vary widely. Yet the evidence is clear that setting hard targets and creating accountability around diversity is one of the only actions that has truly moved the needle. There are many ways to build measurement into your board practice. Many boards now insist that there be equal numbers of female and male candidates presented for every board search; some overcompensate, requiring a female-majority slate, and call for all directors to do their part.

4. Pick for Potential

Boards need a new definition of board-ready. It is conventional wisdom to fill the boardroom with C-suite executives with decades and decades of senior management experience. And yet that is not enough. Our own research and global client experience have found that executives with certain leadership attributes can deliver enormous positive impact, even in business situations or industries in which they have no prior experience. We call these traits, which include curiosity, engagement, insight, and determination, Executive Potential. Betting on potential expands the talent pool automatically and also contributes to boardroom success.

5. Diversify the Pipeline

CEOs must be intentional about developing diverse succession pipelines all the way up to the C-suite. They must create inclusive cultures where women and other groups can thrive and therefore can be retained long enough to be considered for succession to the C-suite and board positions. Companies must also make sure that as women reach the upper levels of management — a time when many women stall — they are supported and developed by mentors and peers alike.

6. Train the Board for Success

It is not enough to simply add fresh faces to a board. Chairs and current directors must also support the integration of new directors after their appointment, both by teaching them the norms of the board and by allowing for the norms of the board to change. New directors should be encouraged to speak out and challenge the status quo. Current directors must understand that having diversity of perspectives and opinions sometimes makes doing the work of the board less efficient, but more effective in the long term — a major change.

7. Professionalize Your Recruiting Process

A recent survey of large U.S. boards showed that 46 percent of organizations with board succession plans said they had no specific process for bringing in diverse candidates. What this means is that recruitment for diversity is often done in a haphazard and unintentional way. Directors must go beyond tapping existing networks and get exposure to a wider pool of board-ready executives. And they must hold themselves and their recruiters accountable for reviewing diverse candidate slates. Diversity must be built into the nomination process at every stage — from briefing to interviewing to selection.

8. Use Both Your Head and Your Heart

Anyone involved in the business of developing leaders must think about both the skills that an effective leader must be able to tick off and the human connection that this leader must also be able to make. The same is true when building a diverse board. Both individual and team dynamics must be part of every director search — not for fit in the traditional sense, but for flexibility.

View the full report on board diversity: https://www.egonzehnder.com/global-board-diversity-tracker